Virality deep-dive - Web2's secret sauce

Architecting viral loops - how to set them up, and what makes them click

Viral loops were Web2’s superpower. While Web1 - largely a network of documents - relied on traditional growth models, viral loops unlocked user-generated growth for Web2 platforms.

I’ve written a lot about vitality over the years and dedicate an entire section in my first book Platform Scale to this topic.

But the topic never grows old.

This edition of the newsletter is a one-stop digest bringing together all of my writings on this topic. And more.

For those who’d like to dig in deeper, I’ve also launched an in-depth online course on this topic (details further below).

So let’s dive right in.

Want to jump over to the course? Access the limited-period launch offer by clicking below:

Deep-dive on virality

“A startup is a company designed to grow fast… The only essential thing is growth. Everything else we associate with startups follows from growth.”

– Paul Graham

And a startup’s potential to achieve hyper-growth and rapid scale is best achieved through virality.

Virality is a phenomenon where a product or a system gains more users on account of its existing users promoting it while using it. Virality is user-generated growth. As the user base grows, so does the ability to grow it further.

Once viral growth sets in, the growth curve crosses an inflection point and takes off non-linearly. As a result, the slope of the growth curve constantly increases while an offering is finding viral adoption. The ability to scale becomes a function of the current user base and hence keeps accelerating of its own accord, as the user base scales.

The secret to viral growth is to rethink growth as a set of actions that users perform.

Viral businesses implement growth within product usage; they leverage users to expose their offering to more users.

Startups that ‘go viral’ demonstrate an ability to scale, which constantly increases. As more users use the offering, the offering’s growth rate increases.

Viral loops

A viral loop is a sequence of user actions that

Enables existing users of a platform to expose the platform to new users on an external network, through mechanisms like referrals, content shares, etc., and

Enables these recipient users to convert to becoming users of the platform, and starting the loop all over again.

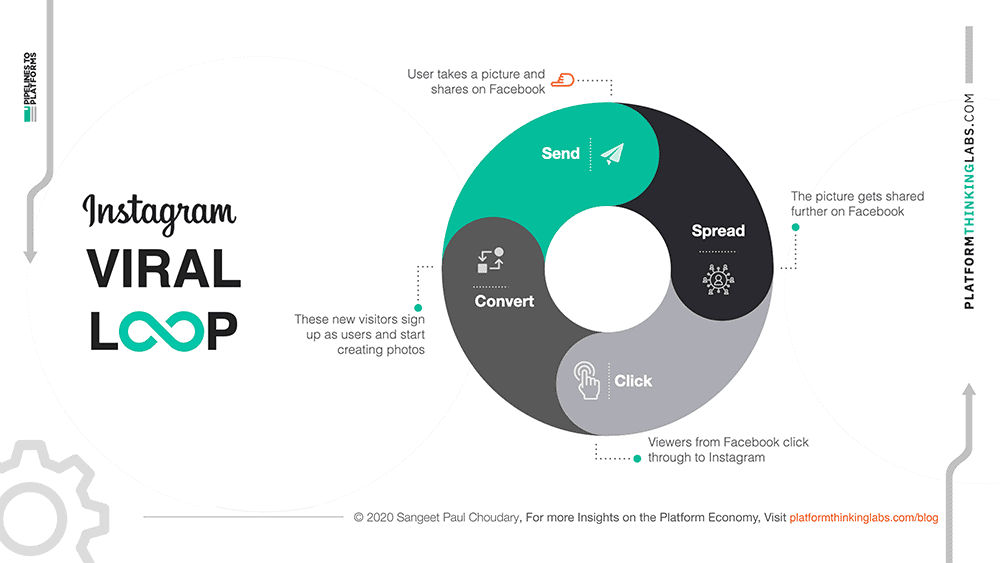

A viral loop consists of four key actions: Send, Spread, Click, and Convert.

1) Send: Maximize outflow of content from the platform

The platform should constantly – and explicitly – promote the creation as well as the spread of new content. As more producers create and share from the platform, new cycles of viral growth get started. Producers need to be encouraged to create new content more often. Moreover, sharing actions should be a part of the creation workflow, where relevant, to ensure that new creations are shared. Instagram’s creation flow clearly demonstrates the importance of this, seemingly simple, design principle. It is equally, if not more, important to identify triggers that lead consumers to share the content that they consume.

2) Spread: Ensure that content spreads on the external network

The next priority for the platform is to maximize the spread of the content on the external network. To a large extent, this spread is determined by the design of the external network. Facebook’s Share, Twitter’s Retweet and email’s Forward functions make content easily spreadable within these networks. However, spread on another network, say the blogosphere, may not be quite as frictionless. Hence, a network’s ability to encourage spread of content may be a key consideration when choosing an external network.

3) Click: Maximize clicks on external network

This requires the platform to incentivize conversions through testing different pitches and calls to action. A/B testing multiple messages may yield different results, and may help the platform to zero in on the right messaging.

4) Convert: Minimize cycle time

Virality works as a cycle with a sender sending out content, the receiver clicking, visiting the platform and eventually converting to the original sender, and starting a whole new cycle. The longer the time this cycle takes on average, the slower is the growth rate of the overall platform.

Further reading: Viral Growth: How PayPal, YouTube And StumbleUpon Gained Rapid Traction Through Piggybacking

If you’re reading this for the first time, go ahead and subscribe:

Viral loop examples

Let’s look at a few examples of companies that created compelling viral loops to scale.

Before it became a social network, Instagram’s app allowed users to take pictures and share them on Facebook. Visitors from Facebook would then sign up and start creating new content on Instagram. In this manner, Instagram rode Facebook’s activity to create a competitor, using this viral loop.

Viral loops often tend to be creator-centric.

Patreon, for instance, allows content creators to earn recurring revenue from their fans.

Content creators start a Patreon page hosting their creations and promote it to their fans via multiple channels. Fans may promote the page further using their social handles. Recipients on these external networks visit the creator’s Patreon page. Some of them may be content creators themselves and sign up on the platform to start their own Patreon page and repeat this loop.

Gumroad has a similar viral loop.

Substack is another great example.

Twitch is a live streaming platform for gamers, where users watch gamers play video games via live streams. Game developers use this platform as a viral marketing channel. Twitch users stream themselves live while playing video games. Viewers further share the streams of their choice with their peer groups. New users sign up on the platform for frequent live streams while some users may move on to streaming gaming sessions of their own.

Virality vs. Network Effects

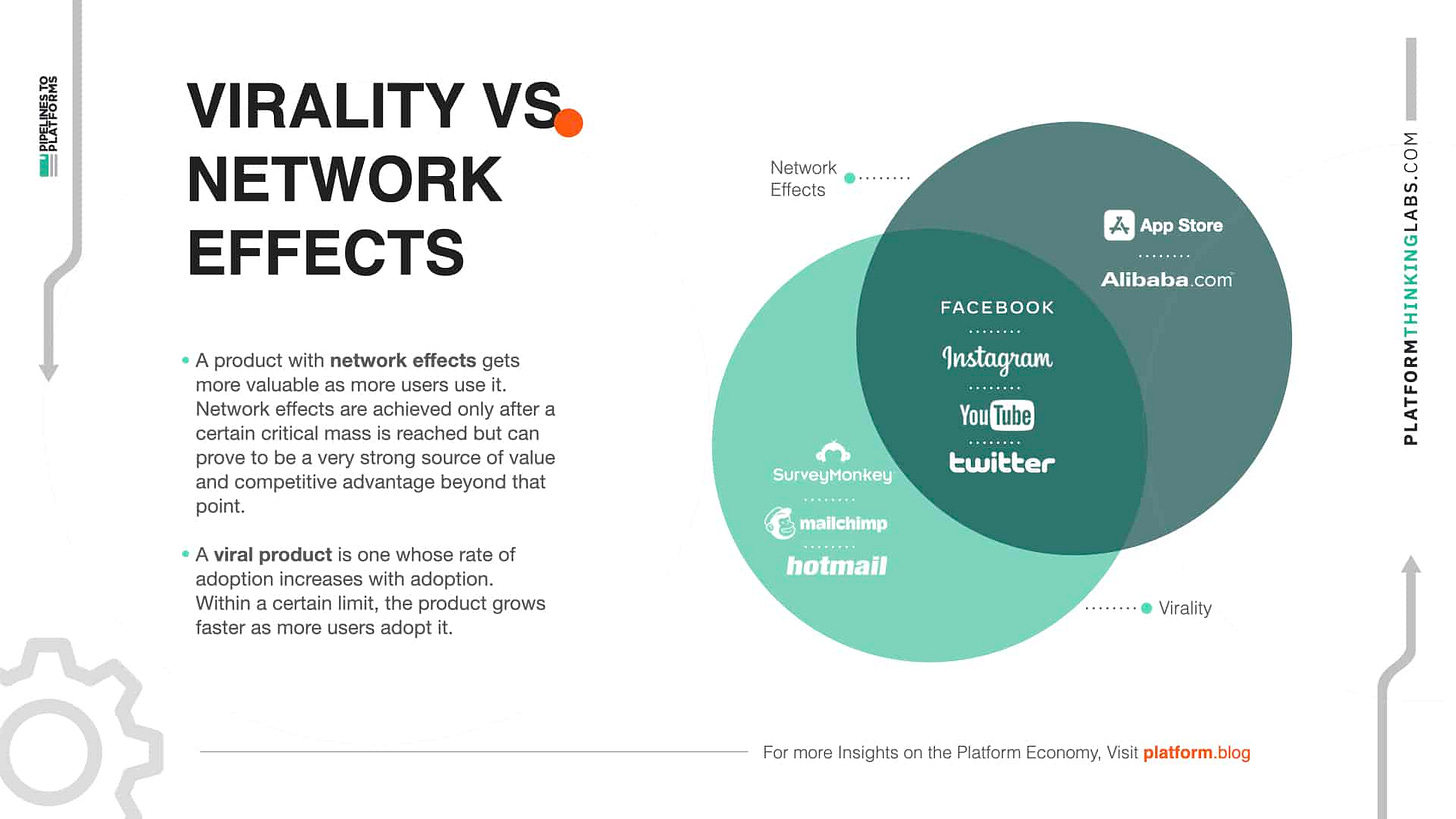

Network Effects and Virality are often confused in the online content world, possibly because the two often occur together and, in such cases, end up reinforcing each other.

Network effects and Virality are, however, completely different. There are many products which have network effects but are not viral. Conversely, many viral products do not have network effects.

Quick Definitions

Network Effects – A product with network effects gets more valuable as more users use it. They are achieved only after a certain critical mass is reached but can prove to be a very strong source of value and competitive advantage beyond that point.

Virality – A viral product is one whose rate of adoption increases with adoption. Within a certain limit, the product grows faster as more users adopt it. There are many products that exhibit virality without exhibiting network effects.

Same Same But Different

Both network effects and virality tend to magnify value and growth respectively as more users use the product. This is probably why the two concepts are often confused. However, as elaborated above, the two actually mean very different things.

In fact, there are many products that exhibit virality without exhibiting network effects. A case in point being email and cross-platform communication products. A key feature here is that they are either interoperable across networks (Hotmail) or leverage an underlying network for both the viral transmission as well as delivery of the value proposition. In the case of SurveyMonkey, Eventbrite etc., that underlying network may be mail, a social network or even a blog.

There are many others that exhibit network effects without exhibiting virality. Products with indirect network effects such as marketplaces may not grow virally. In such cases, network effects are a result of aggregation of the two sides and while each side can be brought on virally through some incentive, it’s very difficult to leverage the indirect network effect to get users on one side to come on through invitations or interactions from the other side.

The following graphic shows a quick overview of how these products stack up and should help clarify the difference between virality and network effects.

Keep digging on this topic.

Here’s your one-stop access to the full structured curriculum on viral growth:

How Virality Works

The design principles for unlocking internet virality lie in understanding contagion spread and the fundamental factors that lead to the spread of infections.

The mechanics of infection spread require four key elements operating in a cycle:

The Host: An infected host sneezes and spreads the germs out in the air.

Droplets: Sneezed droplets carry the germs that spread the infection.

Air: Air acts as a medium to suspend and transfer these infected droplets.

The Recipient: Someone breathes in these droplets and gets infected, in turn.

Subsequently, the recipient becomes the host and the cycle repeats.

Removing even one of these elements from the mix can stop the spread of viral infections. Quarantining, for example, removes hosts. One could speculate, similarly, that sneezing in a vacuum may not have quite the same effect, owing to the lack of air as a transporting medium.

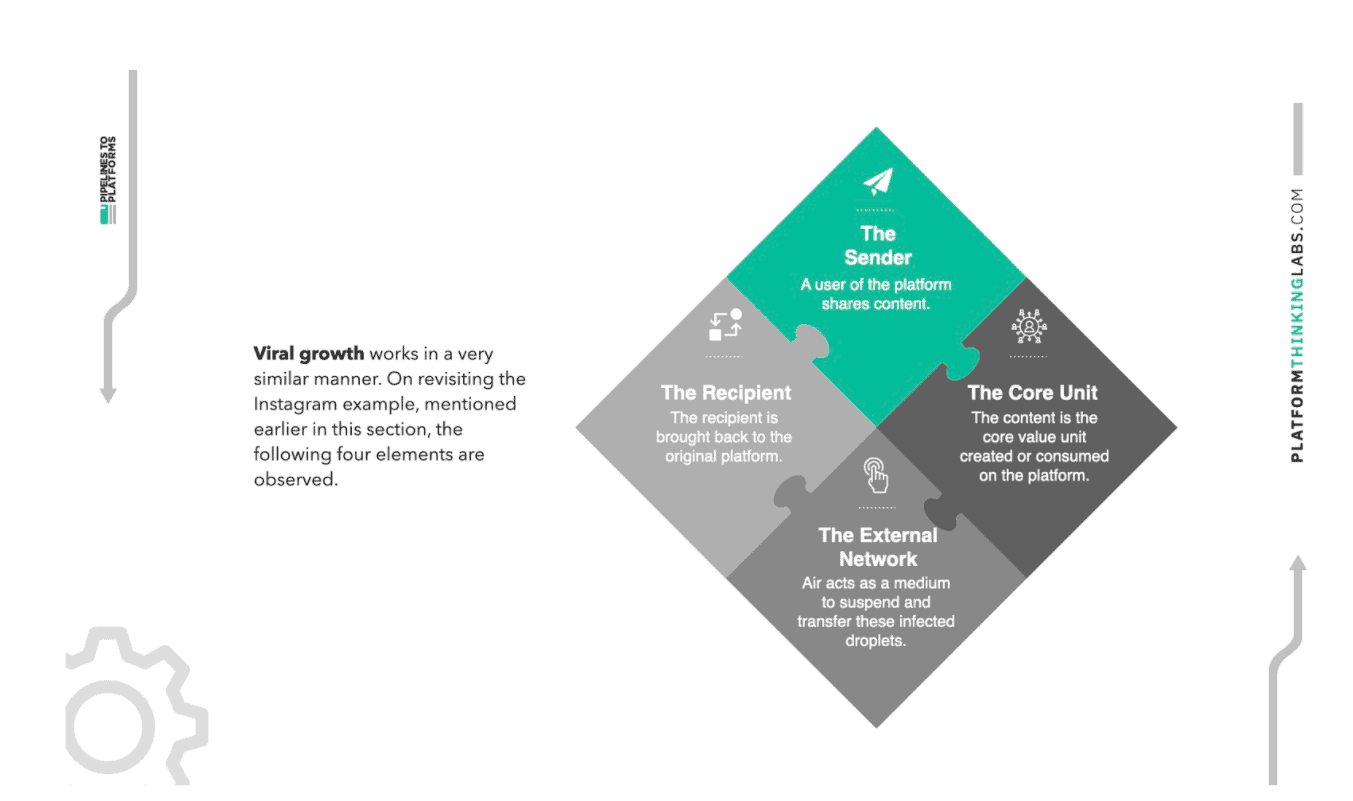

Viral growth works in a very similar manner. On revisiting the Instagram example, mentioned earlier on this page, the following four elements are observed:

The Sender: A user on the platform sends out a message about the platform.

The Core Unit: The message is typically the core value unit that the users create or consume on the platform. A user taking a picture (the core unit) on Instagram shares it on Facebook.

The External Network: These units spread on an external network, connecting people. For Instagram’s growth, Facebook served as a very effective external network, enabling the spread of pictures (units) created on Instagram.

The Recipient: Finally, a recipient on the external network interacts with the unit and is brought back to the original platform. At this point, the user from Facebook gets intrigued by the picture and visits Instagram to potentially create their own photo.

The cycle repeats with The Recipient now acting as The Sender.

Further reading: What is the core value unit?

Incentives

Most viral acquisition is built around incentives. Users are incentivized either inorganically or organically (through product mechanics) to invite other users.

There are various forms of incentives that prompt users to invite other users based on the value that the user receives:

Network Value

Communication platforms (Skype) and platforms that are based on social connections (Facebook, LinkedIn) provide an incentive to connect with others through invites.

Turn-based games like DrawSomething allow users to invite friends because they get interesting opponents in the longer run but also get immediate gratification when the friend plays her turn.

Interaction Value

Every platform has interactions and a currency for those interactions. By far, the most common way for platforms to incentivize virality is to provide users with more currency to engage in such interactions.

PayPal offered $10 to every new person signing up. This, again, drove the invite acceptance rate very high and spurred its adoption.

In social games, players interact with other players using various equivalents of gaming power. These gaming networks typically incentivize users to invite others by providing them more gaming power to get better at those in-game interactions.

Network management on steroids

‘Network management’ software, which allows creators to communicate with, manage and/or monetize their following benefit from virality as well. Consider Surveymonkey and Kickstarter, which both benefit from this dynamic.

Single-Player Value

Platforms that work both in Single-Player mode, as well as Multiplayer mode, may give the user single-player incentives for inviting other users.

Dropbox incentivizes users to invite their friends by giving the user an extra 250MB of space for every accepted invitation. While the users also benefit from having friends on the service when they use it as a collaboration platform, the added incentive of extra space has helped drive virality.

Mutual Value

Users hate spamming friends. It was all fine to begin with when only a few services required them to send out invites, but as every new service asks for an invite to be sent out, users get more discerning. Dropbox, again, incentivizes not only the user but also the invitee when he signs up.

Of course, platforms may use a combination of the above strategies. Dropbox uses a combination of Network Value, Single-Player Value and Mutual Value to incentivize users. Groupon uses a combination of Immediate Value, Interaction Value and, to some extent, Mutual Value.

Further reading:

Incentives to create viral growth

Inherent virality: How To Design Your Platform For Self- Expression

Applying virality to your business

The course on virality unpacks the factors that led to the successful growth of today’s BigTech firms and hyper-growth startups.

The ideas in this course were developed through deep research of a wide range of digital businesses and through actively implementing these design considerations with entrepreneurs building their start-ups.

This course aims to provide a toolkit and a set of design considerations, along with in-depth case studies, to help product managers and marketers plan out and execute towards similar non-linear growth.

In the first Module, we explain the importance of viral growth. In Module two, we explore the common misconceptions that people have about viral loops and why these misconceptions prevent them from executing it well.

Module 3, starts exploring viral loops in detail, first by looking at the structure of disease spread and then applying it back to how digital businesses spread in a networked world.

The next 4 Modules and unpack this viral loop framework in further detail. In Modules 4 to 7, We study the design elements that constitute viral loops.

Module 8 focuses on the optimization decisions associated with viral loops. Module 9 takes a detour to explore the idea of Word of Mouth and leave out creative ways to engineer it.

Finally, in Module 10, we bring together the various elements of this framework to create a cohesive canvas that product managers and marketers can use to take decisions and execute towards viral growth.