You think you are AI-first, but you probably aren't

What Venetian merchants and the railroad pioneers teach us about our current moment in AI

My book Reshuffle is available in Hardcover, Paperback, Audio, and Kindle.

Every startup deck claims to be AI-native.

Every incumbent insists it is becoming AI-first.

But when you press them to explain what those phrases actually mean, the answers tend to collapse into clichés: faster automation, smarter tools, agentic workflows.

Press harder and the answers are always ‘operational’ - a faster move within today’s game.

Most executives talk about AI as if it were electricity: a general-purpose input that can be plugged into any process. The metaphor is convenient but misleading.

Electricity mattered less as an input than as an architecture that redefined how production was organized.

Steam-driven plants had been organized around a single massive drive shaft; electric motors allowed production lines to be reconfigured entirely.

You can’t really be ‘AI-first’ or ‘AI-native’ unless you reimagine your business around the architectural properties of AI.

Through economic history, the organizations that defined new technological eras were rarely those that adopted a new technology, but those that allowed its architecture to reshape the foundations of how they worked, coordinated, and competed.

To understand what it truly means to be AI-native, it helps to step back from today’s slogans and look at the larger structural shifts that have played out whenever a new underlying technology showed up.

This post unpacks these ideas.

What follows is a framework drawn from economic history, identifying four recurring properties that mark when a system is genuinely native to a new architecture:

The redefinition of the atomic unit of value,

The integration of constraints as design features,

The rebundling of organizational systems, and

The reframing of competitive advantage.

From Venetian ledgers to movable type, from the telegraph to containers and barcodes, we see this pattern repeatedly show up. The winners - in every instance - were those who stopped bolting new tools onto old logics and instead rebuilt their systems in the image of the new architecture.

The ideas in this post are based on my new book ‘Reshuffle - Who wins when AI restacks the knowledge economy.’

Architecture eats execution for breakfast

Being architecturally native means designing a system from the ground up around the capabilities and constraints of a new technological input.

Consider the shift to containerization, the story I open Reshuffle with.

For ports that treated the shipping container as merely a tool for the automation of cargo handling, the gains were modest. But for those that rebuilt their operations around the box, primarily, by transforming from just an automated port to an intermodal transportation hub, the container became an engine of transformation around which they reorganized their economy. The container, eventually, imposed a new logic on the entire supply chain, unbundled vertically integrated manufacturing, and reorganized global trade routes.

The advantage did not flow to the ports that handled containers most efficiently within the old frame, but to the ones that redesigned themselves around container standards and positioned themselves at the centre of this evolving ecosystem.

The introduction of the barcode - a story I explore in Chapter 3 of Reshuffle - had dramatically different effects on the fortunes of Kmart - which adopted it as a tool - and Walmart - which pioneered the barcode-native retail architecture.

Kmart saw it as a faster way to ring up purchases, saving a few seconds at checkout. Walmart understood it as an architectural shift. The barcode created a stream of item-level sales data that could be used to reorganize and reorient the supply chain, cross-dock warehouses, and enforce vendor-managed inventory. This resulted in a lot more than store efficiency.

It redefined competition in retail, where power moved from brand manufacturers to data-rich retailers who governed replenishment.

These stories make a case for a broader thesis.

Execution can improve efficiency within an existing frame,

but architecture reshapes the frame itself:

the unit of work,

the organizational logic, and

the competitive landscape.

To be architecturally native is to stop competing on execution within the old system and to rebuild the system around the architecture of the new one.

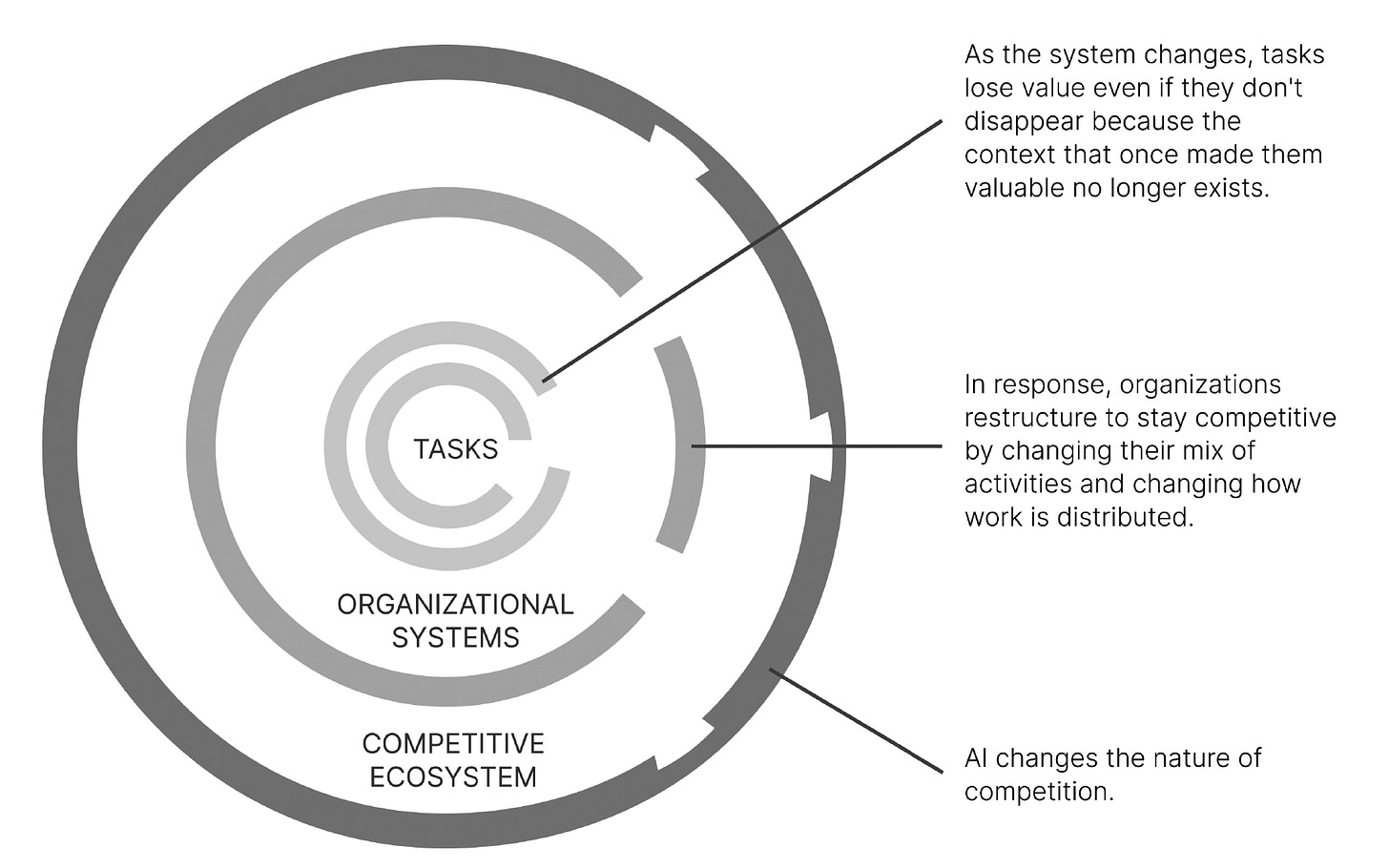

The arc of transformation

Every architectural shift restructures three levels of the system.

The task or the unit of work: The atomic unit of value shifts, enabling new workflows and rendering incumbents’ unit of work obsolete.

Organizational logic: Value creation moves from doing work faster to coordinating and governing work differently.

Ecosystem structure: Entire industries reorganize: who participates, how coordination happens, and where defensibility lies all change.

Figma - the overlooked insight

Last week’s article titled Figma - The untold story unpacks this by explaining why Adobe finds it difficult to compete with Figma because the former uses the cloud as a delivery mechanism while the latter reimagined its entire architecture around the properties of the cloud:

Adobe's design logic is built around the design file (.psd, .ai) as the atomic unit of work.

Figma’s design logic is built around an element in the design file - a button, icon, or type style - as the atomic unit of work.

Changes and permissions could be tracked and managed at the level of a design element. Each element was addressable in a database: change a component once and that change propagated everywhere it appeared. Permissions replaced ownership; engineers, product managers, and marketers could view or comment without being sent anything.

The shift from ‘file’ to ‘element’ as the atomic unit of work had another important effect. Because of the element-based architecture, Figma users could create shared libraries of reusable design components, like buttons, icons, type styles, and color palettes, that teams could use across multiple files and projects. Instead of duplicating these elements in each file, designers simply reference a single source of truth.

This creates consistency, simplifies updates (change once, update everywhere), and enables cross-functional teams to work with aligned visual standards. Shared libraries shift design from isolated file ownership to coordinated, system-level collaboration.

This architecture created strategic separation from Adobe. Adobe used the cloud to deliver the same file‑based logic more efficiently. Figma used the cloud to replace that logic entirely.

By shifting the unit of work from file to element, Figma enabled real‑time collaboration, created a shared design environment that expanded who could participate, and made Adobe’s model feel increasingly constrained by its own architecture.

This simple shift eventually transformed the structure of the entire industry:

In traditional file-based systems, value was created and captured inside closed loops: files lived on local drives, changes were tracked by humans, and tools were optimized for ownership and execution.

The dominant logic was self-contained workflows: a designer edited a file, exported assets, and handed them off, often using proprietary formats inside siloed tools.

But element-level architecture unbundles the design process into modular, reusable pieces. This naturally dissolves the boundary between inside the tooland outside the tool.

With components living in shared libraries and third-party tools can plug into atomic design elements through APIs, interoperability was invevitable.

This shift fractured the vertically integrated model Adobe had dominated. Just as the modular web displaced proprietary desktop software, Figma’s architecture enables a loosely coupled, composable ecosystem of tools. integrating at the level of individual design elements.

Value no longer accrues to those who own the file, but to those who coordinate the system, through reusable design tokens, shared standards, and governance mechanisms.

Figma’s story is a reminder that architectural shifts often look deceptively small.

Moving from files to elements might sound like a technical detail, but in practice, it redefined the unit of work, the basis of coordination, and the structure of competition across an entire industry.

That is the essence of being architecturally native to a new technology:

advantage comes not from adopting a technology,

but from rebuilding your system around the new logic it makes possible.

The atomic unit that rearchitected Venice

Trade in medieval Europe was a bit of a gamble. A merchant might finance a voyage to Alexandria, but his entire fortune was tied to a single, indivisible shipment of metal currency: if the chest was to a storm in the Aegean or to pirates off the Barbary coast, the entire venture collapsed. Risk was binary and concentrated - one chest tied to one voyage, yielding one outcome.

Venice changed that by altering the atomic unit of trade.

In the fourteenth century, Venetian merchants developed double-entry bookkeeping and redefined the atomic unit of commerce from the chest of coins to the balanced transaction.

Each entry in a ledger served as the new atomic unit of trade, capable of being audited, transferred, and reconciled at a distance. Similarly, the bill of exchange allowed money to move as paper promises, negotiable across cities and payable in different currencies. A sack of coins could vanish at sea, but a paper claim could be settled in Bruges or Genoa, unbundled from the voyage that carried the goods.

When the atom shifts, scale and coordination follow new logics. This new atomic unit - an entry in a ledger - enabled the creation of balance sheets, external investment, and eventually the rise of the modern corporation.

This atomic shift transformed the nature of risk. Loss was no longer catastrophic and indivisible; it could be diversified across dozens of ledger entries, pooled across convoys, and insured through collective instruments.

Venice’s muda system institutionalized this principle further: merchants no longer sent ships individually but banded together in state-protected fleets with fixed schedules. The convoy itself became the new organizational system of commerce, turning unpredictable voyages into routinized channels of trade. Pirates might capture a ship, but they could not bankrupt an entire city.

Once risk was unbundled into these smaller, more fungible units, the Venetian economy expanded dramatically.

Families that once tied their fortunes to a single voyage could spread investments across many. Credit could be extended at scale because the underlying records were reliable and auditable. Insurance markets developed, backed by the predictability of convoys and the credibility of the books that recorded their transactions. And most importantly, trade networks could extend deep into the eastern Mediterranean and northern Europe without requiring every transaction to rest on personal trust between two individuals. The ledger and the bill stood in for personal reputation, enabling anonymous exchange at a distance.

The unintended consequence of this shift was that Venice became more than a city of merchants; it became the hub of a financial system. Once recorded in ledgers, wealth could be leveraged to finance new ventures, armadas, and even wars.

By redefining the atomic unit of commerce, Venice transformed risk from a personal gamble into a system-level variable that could be diversified and insured. This unlocked scale, making Venice, perched on its lagoon, one of the strongest economic powers in Europe.

When the atomic unit changes, it reprices risk, restructures coordination, and unlocks entirely new systems of scale and competition.

Being architecturally-native - Four properties

To be architecturally native is to allow a technology’s structure to become the foundation of your system, not an accessory.

Not simply to adopt a technology, but to be defined by it.

The difference between adaptation and nativeness is the difference between layering a new component onto an old design versus allowing the underlying architecture of the system to be reconstituted.

Four recurring properties determine this:

1. A shift in the atomic unit of value

Systemic shifts start with redefining the smallest unit of value.

Complexity is built from atomic units - basic building blocks that determine how larger systems scale. Change the atom, and the system above it must reorganize, as we noted with the example of Figma.

When the unit of exchange or production changes, transaction costs, coordination mechanisms, and value capture shift with it.

Much like the shift from Adobe to Figma, Gutenberg’s invention of the movable type changed the atomic unit of how knowledge was organized and reproduced.

Before Gutenberg, the book was the atomic unit. A manuscript was copied from beginning to end by a scribe, and every book existed as a discrete, indivisible object. If you wanted another, you had to start again from scratch, one page at a time. The cost of duplication was high, and the variation between copies was inevitable.

Movable type unbundled that unit. Instead of treating the book as the smallest whole, Gutenberg treated each character, cast in lead, as the atomic unit of value. By rebundling these atomic units, printers could construct words, sentences, and pages, then disassemble them and reuse the type to build entirely new texts.

Knowledge was no longer bound up in singular artifacts; it became modular, replicable, and composable. That shift allowed for standard editions, catalogs, and the beginnings of an information market where texts could circulate at scale.

The analogy to Adobe’s file versus Figma’s element is obvious. Once the unit was unbundled, everything else changed: workflows, collaboration, industry structure, and even the economics of scale.

2. The embrace of constraints as design principles

Architecturally-native systems don’t treat the limits of a new technology as weaknesses to be engineered away; they adopt them as operating principles.

Systems are defined as much by their constraints as by their capacities. As I explain in Reshuffle, constraints provide stability, reduce degrees of freedom, and direct behavior into predictable patterns.

The muda - Venice’s fixed, state-protected convoy departures timed to seasonal winds - locked merchants into rigid schedules. These constraints reduced movement, but they also reduced piracy risk and synchronized cash cycles, allowing for pooled insurance, enabling Venice to dominate Mediterranean trade.

The telegraph, with its narrow bandwidth, forced traders and journalists into a language of codes and ticker symbols. Brevity became the norm, and from that constraint emerged new grammars of communicating finance and news.

Even containerization required ports and shipping companies to accept the rigidity of standardized box sizes, a compromise that might have seemed costly on the face of it but unlocked global interoperability.

Constraints, when internalized, create predictability and faster learning loops.

3. The recomposition of systems around the new architecture

Once the atomic unit changes and constraints are absorbed, entire workflows and organizations are rebuilt.

Double-entry bookkeeping made it possible for investors in Florence or Antwerp to entrust money to managers they would never meet, because the ledger itself became a trustworthy account of performance. That in turn allowed for external auditing, separation of ownership and control, and the rise of the joint-stock company.

These are second and third-order effects, not always visible at first. Small changes in components or rules can generate large-scale structural shifts.

The barcode at the supermarket checkout was more than a faster way to check out items. It created a continuous stream of demand data, recomposing retail from store-level merchandising to system-level replenishment. Walmart used that flow to cross-dock warehouses, enforce vendor-managed inventory, and reverse the traditional balance of power between retailers and suppliers.

In the hands of an architecturally-native player, a simple technology becomes the basis for rethinking how an entire organization coordinates and governs itself.

The rise of the railroads alonside the telegraph is possibly the best example of such a systemic shift.

Before the railroads, most businesses operated at a local scale. A factory might employ dozens of people, a trading house might operate a few routes, but management could be handled directly by owners or a handful of trusted clerks. Information moved at the speed of letters and couriers, and decision-making was largely in-person.

The railroad changed that, and the telegraph made it possible. Rail lines stretched hundreds of miles and trains ran simultaneously in both directions, forcing the need for precise coordination. A single delay in one town could have larger effects across others. Without real-time communication, chaos and collisions were inevitable.

The telegraph solved this coordination problem. It allowed railroad companies to centralize dispatching: trains could be scheduled, rerouted, or held back based on telegraphed updates from stations along the line. To make this work, railroads also needed standardized time, which is why the U.S. and Britain adopted time zones, an institutional response to the demands of rail and telegraph integration.

But perhaps the most enduring change played out organizationally. Railroads became the first truly large, geographically dispersed corporations. Owners could no longer manage by proximity, so they invented new structures: regional divisions, professional managers, and reporting hierarchies.

These were the foundations of what Alfred Chandler later called the visible hand or more bluntly, the rise of managerial capitalism.

4. Reframing of competition

Once a new architecture takes hold, the game itself changes.

In the age of railroads, competition moved from who had the fastest locomotive to who controlled the timetables and the through-rates.

Containerization rewrote shipping competition from handling capacity at individual ports to the efficiency of end-to-end intermodal routes.

Each time, incumbents who clung to the old axis of competition - whether engine horsepower or port size - found themselves blindsided by rivals who had redefined the game.

Shifts in architecture change the system’s boundary conditions and the criteria on which firms differentiate and capture rents. The Venetian merchants who embraced convoys timed to seasonal winds illustrate this best. The competitive axis shifted from individual risk-taking to collective risk-pooling and insurance capacity, making Venice the most powerful merchant shipping hub of its time.

These four ideas determine how workflows, organizations, and business models restructure around new technologies - not based on their performance as inputs as much as around a new logic of value creation across the system.

Reshuffle is now 1 month and 50 reviews old

Here’s one:

If you’ve enjoyed the ideas in this post, go ahead and get the book to access the larger framework!

The slow incumbent fallacy

When new architectures emerge, incumbents rarely stumble because they lack speed, vision, capital, talent, or the will to compete.

They falter because their existing systems are locked into a particular logic, and abandoning that logic would mean unraveling the very structures that sustain them.

Architectural advantage, once embedded, is both an asset and a trap.

Adobe illustrates this dilemma. Its dominance was locked-in to the logic of the file as the atomic unit of design work.

To abandon that structure in favor of Figma’s element-based architecture would have required dismantling the entire system of connected tools, workflows, and customer habits that Adobe had cultivated for years.

Path dependence amplifies this lock-in. Factories in the early era of electrification often installed electric motors but left their layouts unchanged, still organized around a central shaft designed for steam. Their workflows, contracts with suppliers, and even union agreements were tuned to the rhythms of the old architecture.

The incumbent is rarely blind or inert. They see the new architecture. But to adopt it fully would mean rewriting their workflows, revenue streams, and identity.

We often over-emphasize the need for operational agility, suggesting that incumbents fail because they move slowly.

The real reason incumbents struggle is not operational agility, it is structural agility - the inability to unlock their existing locked-in architecture.

Adopting ‘agile’ will not solve the real problems your organization faces - that of structural agility.

A final diagnostic

If you really believe you’re pursuing an architecturally-native approach, ask yourself the following questions:

Atomic: What new atomic unit replaces the old one?

Constraint: Which hard constraints are you embracing as design?

Rebundling: Which workflows, budgets, and authorities are rewritten around these new constraints?

Reframing: On what new axis of competition will you win, and which incumbent moats become irrelevant?

Reshuffle on the podcast circuit

I’ve been doing a range of podcasts on the ideas in Reshuffle, including BCG Ideas and Thinkers, AI@Wharton, the Futurists pod, and several others.

If you’d like to discuss Reshuffle on your podcast or feel it should be brought to a podcast in your network, just hit reply and let me know.

In the meantime, here’s one pod to explore some of the ideas in the book further:

Choudary’s short test (the "you" is a hypothetical you):

1. Atomic?

Are you treating the AI prompt as a one-off, or is the prompt *itself* the new unit of value (token-level, element-level, reusable, composable)?

2. Constraint?

Are you merely tolerating hallucinations or building your product *because* of them—designing workflows that treat probabilistic text as a feature, not a bug?

3. Rebundling?

Which budgets, meetings, job titles, and approval gates vanish when an AI loop replaces human coordination steps?

4. Reframe?

Which incumbent advantages (brand trust, file ownership, human service layers) become irrelevant when speed of iteration and prompt reuse outshine them?

If you can’t answer all four in one sentence, you’re still bolting the AI onto a legacy axle.

To check my understanding:, and maybe to state the Bleeding Obvious™️: this reference to architecture aligns pretty well with Carlota Perez’ “techno-economic paradigm”..(?)