Chegg, ChatGPT, and the changing nature of change

Change is no longer constant, when the nature of change itself changes

Chegg is the first prominent victim of ChatGPT.

Chegg - which started life as a messaging board, moved on to textbook rental services, and eventually shifted gears to providing online homework help - has lost more than 99% of its value since its peak a couple years back.

But Chegg’s story is interesting not so much because it represents the disruption that AI can bring to a well established company.

Chegg’s story is far more interesting because it’s emblematic of how uncertainty operates in our world today.

Chegg… and change

Chegg’s trajectory over the past 5 years highlights a key shift in the type of uncertainty modern businesses face today.

Chegg started life as a textbook rental service for students. In 2005, it acquired Cramster and shifted to providing pre-written answers to frequently asked homework questions.

Over the next 15 years, Chegg scaled this model with (1) hiring thousands of contractors, primarily in India, to answer questions posted by students, and (2) packaging this on-demand homework help as a subscription.

That was till 2019.

Since 2020, Chegg’s story is the story of how business success is governed more by environmental uncertainty and the options it affords (or cuts off) than by a business’s operational chops.

First, during COVID-19, Chegg experienced an unexpected surge in usage as remote learning became the norm. Students stuck at home took to the homework help platform.

But just as the Covid bump receded with the rapid adoption of generative AI, its subscriber base quickly plummeted.

Chegg was neither overtly responsible for its success nor was it entirely at fault for its failure.

When change itself changes

Chegg’s story highlights a conundrum that many business leaders face today. I’ve advised CEOs of banks, retailers and telcos over the past 15 years and a repeated pattern you’d hear was this - ‘we didn’t do anything wrong, but somehow, we lost’.

You’ve heard that before - Stephen Elop at Nokia.

Change and uncertainty are all around us. But the nature of change itself has changed.

Traditionally, businesses dealt with operational uncertainty, which operates within a known structure, where the fundamental “rules of the game” remain stable.

Operational uncertainty involves unforeseen challenges within a stable environment—companies may have to adjust strategies, but the playing field - and, more importantly, the game they are playing - remains familiar.

Today, however, companies are faced with a far more difficult problem - structural uncertainty.

Structural uncertainty reshapes the entire playing field itself, and with that, you are often left playing the wrong game.

This type of uncertainty doesn’t just change how companies compete—it changes what they are competing for or against. This is what Covid did to travel and ChatGPT is now doing to Chegg. Why pay for delayed answers which may not be perfect when your AI assistant gives you instantaneous and far better answers.

Operational uncertainty can be addressed by small tweaks - improving the quality of people writing answers on Chegg, improving the curation systems, etc. Structural uncertainty often leaves you fixing problems with the wrong tools.

The key mistake leaders make when confronted with uncertainty is they try to solve structural problems using operational responses.

Change is not just more and faster, it’s different

What do operational responses to uncertainty look like?

Most companies today understand that change is faster and more constant than ever. And they’ve become adept at handling it.

They talk about agility - and create processes that can respond quickly. There’s a lot of talk on resilience - which will help them power through that change.

But all this talk of agility and resilience assumes that the only thing that’s changing is the rate and quantity of change. Things are becoming more volatile, moving faster.

Tools that deliver agility, even resilience, provide operational responses to change.

A structural response to change needs

(1) A rethink of the playing field, and

(2) Reimagining the winning game within it

Rethinking the playing field

How do you reimagine the playing field?

First, you dispel traditional notions of competition and start looking at substitutes instead.

Operational responses can be directed at competitors playing the same game. But substitutes demand structural responses.

A better homework prep service is a competitor. An AI assistant is a substitute.

A call center with better operational metrics is a competitor. A customer support solution fitted with AI agents is a substitute.

A company outsourcing to get work done is using operational tools to compete. A company rewiring its operations around AI agents (read more here) is using a structurally different solution to create a substitute.

Stay focused on your competitors and watch substitutes eat your lunch.

Reimagining the winning game

Once you’ve figured structural shifts that may give rise to new substitutes, what options do you have?

In some situations, as with Chegg in the wake of ChatGPT or the travel industry during Covid, you may be structurally disadvantaged because the discontinuity either adversely affects your demand or ‘unfairly’ supports the new structure of substitute supply.

The challenger, in this case, develops a structurally superior model. In the case of ChatGPT, that is the world’s knowledge at your fingertips with language comprehension wrapped around it. In contrast, Chegg provided you slower answers from someone sitting across the world vigorously trying to answer your question. Both the scope and speed of solutioning changes.

This is not always the case. Not every shift brings with itself a structurally superior solution. For instance, the rise of sensors brought in many new startups that could retrofit sensors and offer analytics but the new business model wasn’t structurally superior. Established hardware manufacturers working with high fixed costs and a large base of customers protected their turf while startups looking to offer machine usage analytics rapidly realised that there were no barriers to entry in that business.

So challengers don’t always emerge with a structurally superior solution.

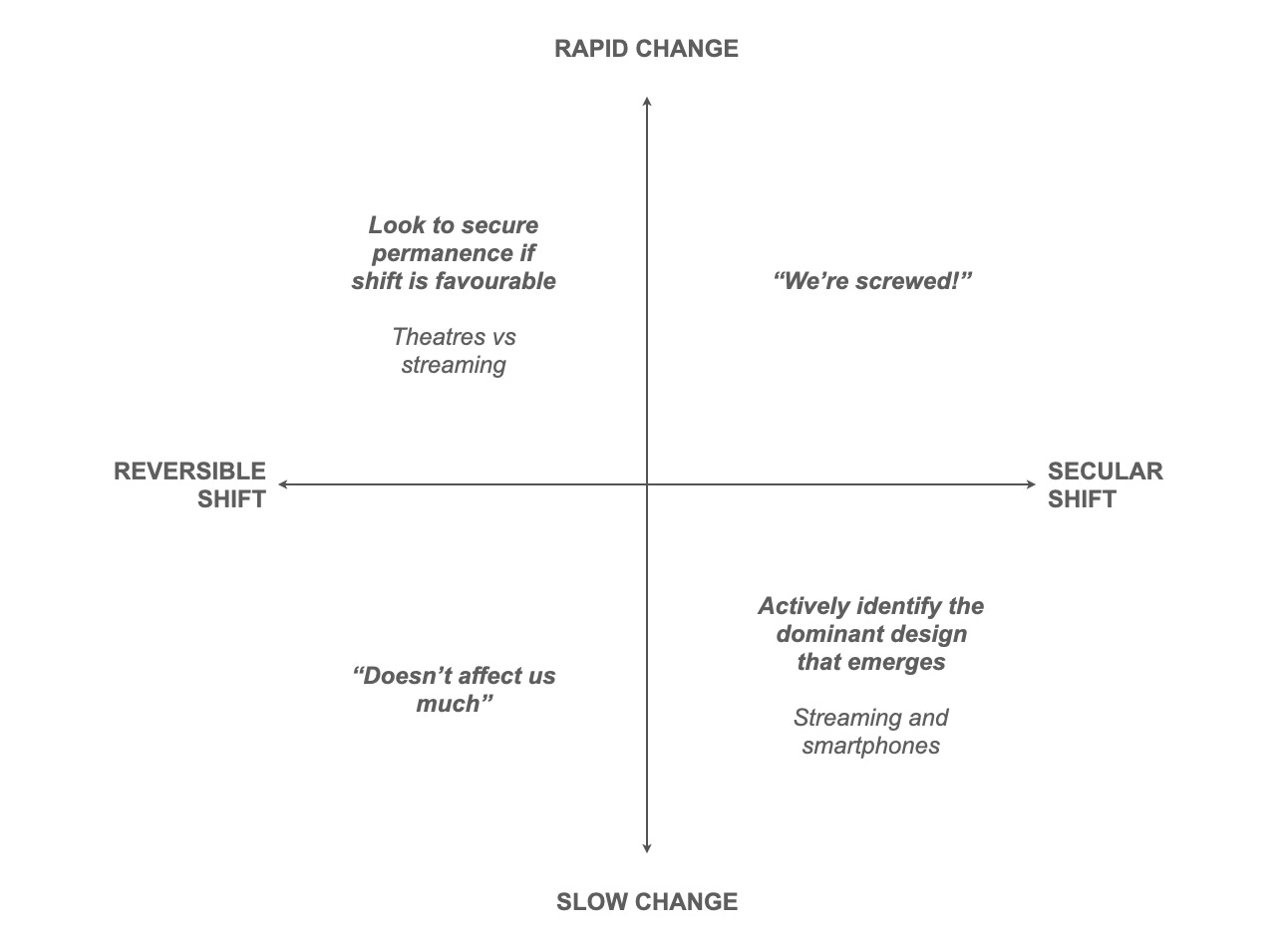

But when they do, the factors determining the fate of the incumbent are

(1) whether the shift is reversible (as with Covid’s impact on travel) or permanent and

(2) whether change happens rapidly (Covid again) or slowly.

In fact, the two scenarios where demand for your offering changes but where you still stand a chance at winning through a superior solution are:

The shift is sudden and reversible but can be harnessed towards permanence

The shift is slow and secular

Of course, nothing is permanent. Temporary vs permanent, here, is more a function of how reversible the effects of the shift are.

1 - Slow but secular

Blackberry had a few years to react to the iPhone. But it was held hostage by its architectural choices.

Blackberry didn’t necessarily win or lose because it failed to open out to developers or because it failed to understand the importance of the smartphone.

It failed because it had structured all its architectural choices around maximizing security for a communications device.

The iPhone wasn’t a communication device. It was a computing device where the phone was reduced to an app. The iPhone also introduced a new dominant design - a brick-like phone format that survives to this day. Almost all phones today resemble the dominant design introduced by the iPhone. Prior to the iPhone, there were a range of phones with different designs in the market.

This dominant design - a brick-like structure with a tray of apps and a screen that responded to finger gestures - introduced computing on a small screen.

But for Blackberry to emulate that, it needed to let go of many design choices that had been made over time to progressively create the most secure phone.

Incumbents often fail not because they are slow to react but because they are bound by a tight system of design choices that they’ve made over time.

This also explains why the new design was never successfully adopted by the leading incumbents of that time - Nokia, Blackberry, Motorola, Sony etc. Instead, a whole new range of smartphone manufacturers - unencumbered by those design choices - emerged as the new smartphone manufacturers.

When change is slow and secular - often spanning a couple of years - incumbents need to give a good hard look and see if a new dominant design emerges and the trade-offs they would have to manage to adopt that new design.

2 - Rapid but reversible

And then there’s change that’s rapid but also reversible. If it’s working in your favor, think of how you could make it permanent.

Covid was one such example. A sudden change in the nature of demand.

How do you secure a permanent shift when the change in demand-side factors is only temporary.

You create supply-side factors that uniquely benefit from the blip in demand-side factors, but which can be leveraged even once demand-side factors reverse.

The quick commerce example from my previous post is one such example.

India’s local ‘kirana’ stores have withstood many cycles of change. But they’ve finally bowed to Quick Commerce. Nearly half of ‘kirana’ sales have now been replaced by quick commerce, by some measures. More than 200,000 ‘kirana’ stores have now shut down.

Covid lockdowns drove the rise of quick commerce, yet the model has sustained and thrived far beyond that temporary discontinuity.

As I explained in the last post, this happened because quick commerce delivered a structural response to secure that shift. It created supply-side factors that made it fundamentally more convenient to keep using the model even after lockdowns ceased and the pandemic was well into the rearview mirror.

As I explained in the previous post:

Advantage is created by securing micro-warehouses, or “dark stores,” in those areas. By positioning small distribution hubs close to dense clusters of demand, quick commerce companies can meet the intense need for rapid fulfillment more efficiently than traditional e-commerce models.

Once a company establishes these local warehouses, the operational model shifts.

Once a company invests in strategically located hubs, those fixed costs—rent, inventory, and infrastructure—create a barrier for competitors.

Each additional delivery then becomes cheaper, which increases demand and lowers costs even further.

Quick commerce isn’t about network effects; it’s about optimizing real estate to build advantage in specific high-density areas.

The defensibility of quick commerce lies in the fixed infrastructure—the micro-warehouses. It is the density of demand that drives efficiency and makes the model work, not the size of the network.

If change is rapid but reversible, try to find a way to use a demand-side discontinuity to invest in creating supply-side advantage that outlasts the change and sustainably delivers a superior model.

The quick commerce players in India did that. Streaming players during Covid did something similar when they gained negotiating power over theatres. Direct-to-streaming releases outlasted Covid and release windows - during which theatres prevented movies from being released on alternate channels - have progressively gone shorter.

What stays the same

You’ll note that I’ve deliberately tried to skip arguments around what AI will eat for lunch and what it won’t. AI is a powerful force of change. But it’s one of many that’s reshaping the playing field. These forces - in so far as they are structural - have accelerated over the last two decades - a natural consequence of (1) globalisation, (2) connected markets thanks to the internet, and (3) changes in industry economics owing to cloud computing and X-as-a-service. If the world was not so connected at all those three levels - trade, markets, and enterprise - the effects of technological shifts wouldn’t be quite as complex.

What matters then is to have a clear thesis for change.

If change is inevitable, how do we evaluate the quality of change?

Which change is worth responding to and which one isn’t?

Where does change create an opportunity for structural advantage, and where does it leave us far behind without hope of catching up?

That’s the real story of Chegg and ChatGPT… and of the many such dilemmas we will continue to confront in the years ahead.

As always, just brilliant. Thank you

Another great article