The ONDC conundrum: Where protocols win... and where they don't...

The three laws of protocol economics

India’s ONDC (Open Network for Digital Commerce) has been the most ambitious decentralized alternative to the centralized e-commerce marketplace model pioneered by Amazon and others.

Yet, it has (thus far) struggled to fully deliver on its promise to reorganise the commerce ecosystem through a protocol-based approach.

To many, this is even more confounding when compared with the massive success of UPI, another seemingly similar protocol for orchestrating payments, which has transformed financial services (to the extent of digitizing roadside begging) across India.

The key to unlocking ONDC’s potential may well lie in unpacking the economics of protocols and open networks.

This is an ambitious, far-sweeping analysis… and there’s a lot to unpack here… a lot that runs counter to current conventional wisdom on the economics of open networks.

This analysis is not a comment on the commendable efforts behind an ambitious initiative like ONDC as much as it is on the erroneous ways in which media, investors, and analysts interpret the mechanics at play.

There are three parts to this deep-dive:

The fallacy of the unbundling + interoperability argument

Factors that determine whether protocols win or lose

Determining which players win and which ones lose in a protocol’s ecosystem

Let’s give this a spin!

A quick primer on ONDC

If you know about ONDC, feel free to move on to the next section.

But if you don’t, a picture is worth a thousand (or 200) words… so I’ll skip those 200 words and drop this picture here instead:

Essentially, ONDC provides a protocol-based organization of an open network of buyer and seller side interfaces and services instead of one centralized platform that bundles all those services together.

Instead of one single platform managing buyers and sellers, buyer-side agents can onboard buyers, seller-side agents can onboard sellers, and the protocol can settle transactions.

Protocols = Unbundling + Interoperability?

At the heart of protocol economics lies unbundling. I’ve written about this before in Unbundling the Unbundlers:

Marketplaces bundled demand-side onboarding, decision support systems, and tools with supply-side onboarding, decision support systems, and tools. Protocols unbundle the two.

For instance, a marketplace like Ebay bundles seller onboarding, seller analytics, buyer onboarding, buyer decision support, search functionalities, and exchange infrastructure. All these components will be unbundled.

As a result, we move away from central market-maker architectures to decentralised agent-based architectures, all coordinated by a shared, common protocol.

All of those points broadly hold true.

In fact, this unbundling playbook played out to perfection for India’s protocol economy poster-child, the Unified Payments Interface (UPI). ONDC is often compared and contrasted with UPI so it’s worth getting to know UPI as well.

UPI provides protocol-based orchestration for inter-bank peer-to-peer transactions, using a payments identifier (UPI ID) linked to your mobile phone number. UPI is a great example of unbundling (of the custodianship of money linked to an account from the payments linked to an ID) and interoperability (using a unified identifier that works across banks).

The logical fallacy of the unbundling argument

Analysts and pundits explaining value creation with ONDC rely on the following core argument:

ONDC creates value through a combination of unbundling and interoperability.

The proposed path to success is:

Step 1: Unbundling (of the commerce value chain)

Step 2: Interoperability (as specialized players emerge)

Step 3: Success (as interoperable players deliver the end-to-end value chain)

There are three fundamental flaws with this argument.

And these three factors explain why unbundling works in favour of UPI, but almost works against ONDC.

To make all this a tad more dramatic, I’d like to now propose the three laws of protocol economics.

The first law of protocol economics

First, unbundling - in general - increases coordination costs.

This brings us to the first law of protocol economics:

A protocol creates value through unbundling to the extent that it can absorb and resolve the coordination costs originating from unbundling.

Unbundling and interoperability do not magically lead to success.

In fact, unbundling + interoperability can create a nightmare if the coordination costs aren’y sufficiently resolved.

The lego comic picture below - churned out by Midjourney - illustrates what such a coordination nightmare would look like.

This is why protocols are not always the right solution.

The second law of protocol economics

What, then, determines how high these coordination costs are?

This brings us to my second law of protocol economics:

The more the number of steps in the value chain you unbundle, the higher the coordination costs.

In the case of UPI, unbundling is valuable because it's largely occurring across two layers only: the sending bank and the receiving bank. The coordination costs are minimal and are sufficiently resolved by the protocol.

However, ONDC unbundles the commerce value chain across many more layers (seller onboarding, inventory aggregation, search, fulfilment, returns, dispute etc.).

In this case, unbundling increases coordination costs to an extent that can't be resolved by the protocol alone.

Coordinating across seven specialized layers of the value chain is orders of magnitude more complex than coordinating across only two layers (as with UPI).

This coordination failure translates into a poor consumer experience. The buyer may effectively find inventory but may have a poor fulfilment experience. The fulfilment may work well but the returns may not. The returns may work well but a dispute raised may not be sufficiently resolved.

With a centralized platform, a single entity coordinating across these steps successfully absorbs the coordination costs. With a protocol, every additional layer unbundled creates a non-linear increase in coordination costs.

The third law of protocol economics

There’s a final reason that ONDC struggles where UPI is successful.

And with that, the third law:

A protocol’s ability to absorb coordination costs is inversely proportional to the degree of variability in use cases it needs to directly coordinate.

Payments is horizontal and has a narrow degree of variability. The payment flow for buying a toothbrush is similar to the payment flow for buying plumbing services. The commerce flow for the two are vastly different.

The use case that UPI supports in payments is very well suited to protocol-based mediation. This is also why even in platforms, it is so difficult to unseat payments players, while vertical competitors emerge all the time to compete with Ebay and Amazon.

The criterion ‘directly coordinate’ is crucial here. Yes, payments are embedded across a wide variety of use cases, but the payments flow itself is relatively narrow with low variability and high standardization.

Commerce extends across a variety of varied use cases. Vertical use cases require specialized mediation. This is why vertical marketplaces repeatedly come up and compete with Ebay and Amazon, despite their horizontal dominance.

This combination of vertical specificity (high variability) and high coordination costs makes ONDC especially poorly suited as a protocol-only solution to commerce.

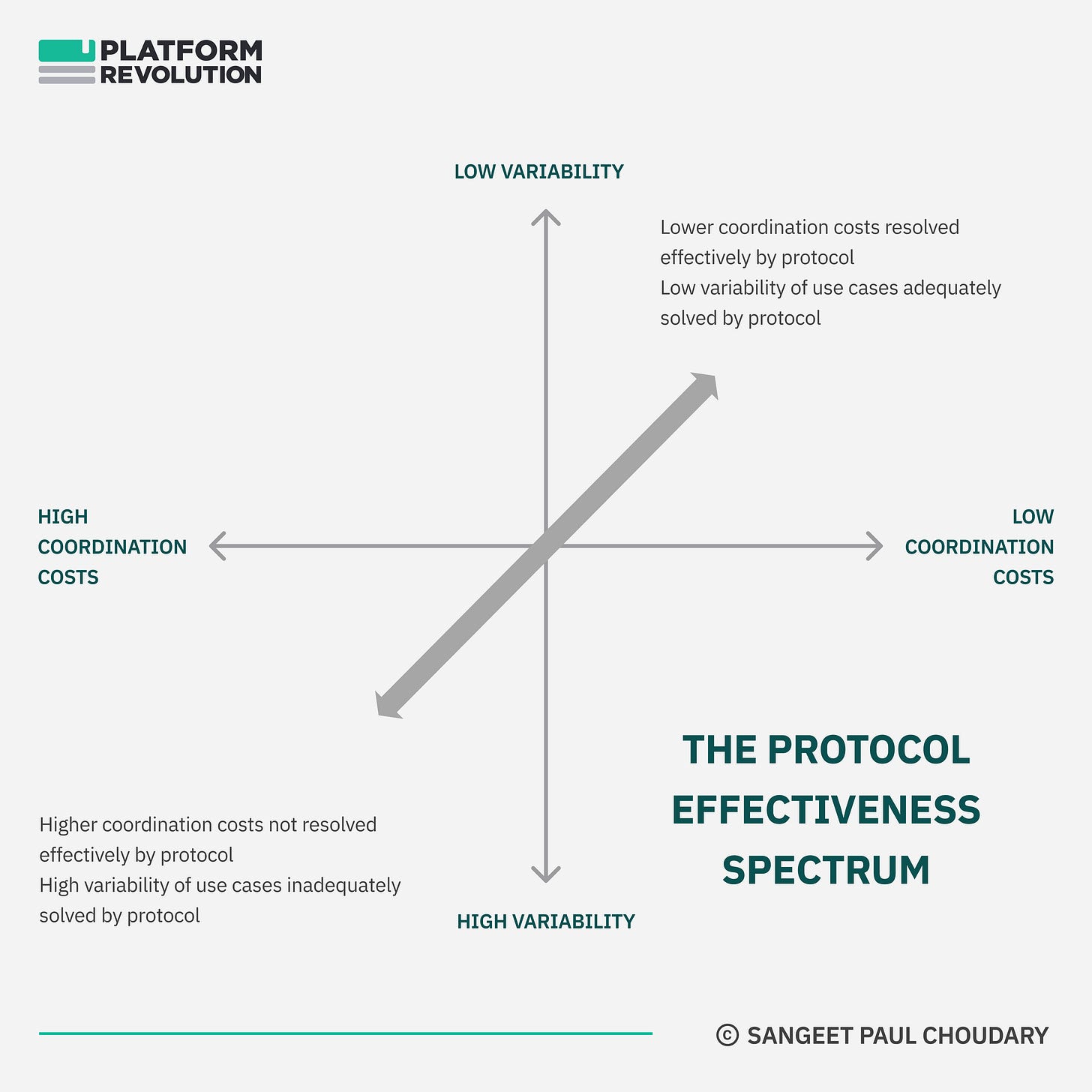

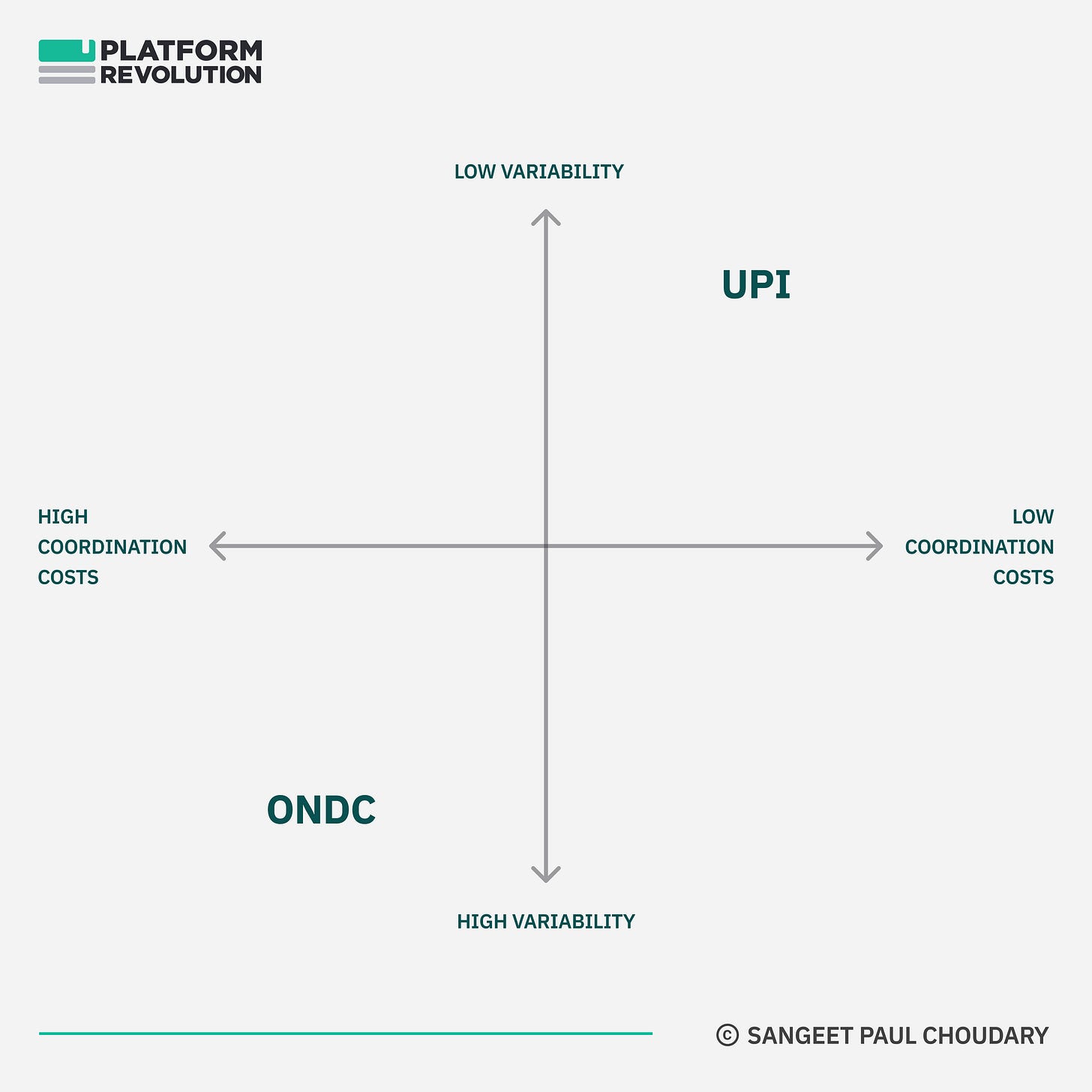

The protocol effectiveness spectrum

Bringing all this together, we realize that protocol effectiveness may lie across a spectrum - from weak to strong.

Here, I’m specifically referring to a protocol’s effectiveness at coordinating market activity.

The lower the variability in use cases and the lower the coordination costs, the stronger the protocol’s effectiveness at mediation.

The higher the variability in use cases and the higher the coordination costs, the weaker the protocol’s effectiveness at mediation.

This explains why ONDC struggles while UPI wins.

UPI sits at the ‘strong’ end of this spectrum.

ONDC, conversely, is stuck at the weak end of the spectrum.

The entire argument of unbundling and interoperability actually works against ONDC, not in its favour.

Know someone who should be reading this?

Solving for protocol effectiveness

Well, how do we solve for protocol effectiveness?

You can either work to reduce coordination costs…

Or reduce the variability in use cases supported.

Moving along both axes helps us ascend the protocol effectiveness spectrum.

Let’s look at both options in turn as potential solutions to the ONDC conundrum.

The insufficient network effects of platforms

Why do offline retailers struggle to compete with online marketplaces?

Platform pundits would have you believe that the answer lies in network effects.

The larger the scale and scope of inventory, the greater the choice for consumers, the higher the network effect.

This begs the question - Why can’t offline retailers run the same flywheel?

Yes, the network effect is necessary. But it isn’t sufficient to win the online marketplace game.

This brings us to the second (and sufficient) condition:

Vertical integration across supply chain data!

Fulfilment, returns, and dispute resolution are three key factors that determine consumer experience and transaction economics for online marketplaces. Inventory choice is necessary but not sufficient.

And this is where offline retailers struggle.

First, managing fulfilment to the home requires management of 70 different use cases (leave it with my neighbour, use my smart lock, don’t play with my dog, the works) as compared to store-based fulfilment.

This involves a fundamentally different supply chain. Offline retailers struggle because their distribution centres and supply chains are geared towards in-store fulfilment, which involves far fewer (and relatively more static) use cases.

Second, fulfilment, returns, and dispute resolution cannot be delivered at scale without supply chain data gathered through vertical integration from the warehouse to the home. Supply chain data aids superior stocking and routing and superior supply chain responsiveness, in general.

None of the traditional retailers have supply chains geared towards this.

The real reason offline retailers can’t even get into the playing field - ironically - isn’t so much the network effect. It is the fact that they have far less vertical integration across supply chain data and are unable to support the complexity of at-home fulfilment and returns.

This brings us to our first solution to increasing protocol effectiveness at market mediation.

Vertical integration in the ecosystem.

Ironically, a protocol needs vertical integration in its ecosystem to resolve the high coordination costs that emerge.

In the case of ONDC, this may especially apply to returns, fulfilment, and dispute resolution. Opening out these functions for the ecosystem to find its own solution increases coordination costs instead of reducing them.

While the increased coordination costs of open inventory can be easily absorbed by the protocol, the increased coordination costs of open fulfilment and dispute resolution are too high to be resolved through a protocol.

As a result, the ONDC ecosystem still struggles with fulfilment, returns, and dispute resolution. The coordination costs of managing them through a protocol-mediated ecosystem are way too high.

Again, these coordination costs don’t emerge with UPI.

Where protocols win… and where they don’t

The other way to increase protocol effectiveness is to narrow down scope and reduce variability of use cases.

And ONDC seems to have done that by focusing on food delivery and grocery.

Unfortunately, those two categories are least amenable to protocol-based mediation.

Protocols are most suitable to market mediation in categories which have

(1) differentiated inventory and

(2) high margins.

Food delivery, ride hailing, and grocery are quite the opposite.

First, owing to the commoditized inventory in these categories, a good consumer experience (= faster delivery time) is determined more by routing and delivery package stacking algorithms than by adding additional restaurants (inventory aggregation). The protocol advantage of open inventory is irrelevant in these categories. In fact, these commoditized inventory categories win precisely through the vertical integration of data from the warehouse (or kitchen) to the home. That data helps improve routing of delivery drivers, bundling multiple deliveries along optimal routes, and even optimal location of cloud kitchens to minimise delivery time.

More on the economics of vertical integration of supply chain data here:

Second, these categories lack the margins required to resolve the coordination cost emerging from orchestrating multiple players across the value chain.

These low-margin, commoditized categories are best served through vertical integration, not through protocols.

Decentralize… to re-centralize

In summary, there are two key factors that determine ONDC’s effectiveness as a protocol-based open network:

Resolving coordination costs in the ecosystem by fostering at-scale, vertically integrated players at and across activities where coordination costs are too high.

Focusing on categories that support differentiated inventory, support margins high enough to absorb coordination costs, and ideally benefit from local network effects.

Managing protocols is not just a question of where/what you decentralize.

It is as much (or even more so) a question of where/what you centralize.

With protocols, centralization is a feature, not a bug

Protocols decentralize.

But decentralization doesn’t exist in isolation.

Centralization and decentralization co-exist.

Protocols that de-centralize market making will shift the locus of centralization to another point in the value chain.

Consider email for example. Theoretically, anyone can establish and run their own email server.

Yet, the email provider ecosystem is one of the most concentrated ecosystems. A handful of large BigTech firms (most notably Google and Microsoft) control all service provisioning.

This is largely because the complements that make email useful - spam filters and storage - are controlled by these players and benefit from the feedback loops of learning effects (in the case of spam filters) and scale effects (in the case of cloud-hosted storage).

As far as protocols go, centralization is a feature not a bug.

Protocols decentralize… until they re-centralize.

Winning and losing as an open network

This brings us to an important juncture.

Will ONDC win?

The answer, as always, is ‘it depends’.

If ONDC’s goal is to decentralize and unseat large players in commerce, the answer, ever clearer, is no. If anything, it will further strengthen their business models, as I explain shortly.

If ONDC’s goal is onboarding offline sellers and democratising access to their inventory, the answer is most likely yes.

Winners and losers in the ONDC ecosystem

The unresolved coordination costs in a protocol’s ecosystem will eventually drive new vectors of centralization.

As I explained in How to win at Gen AI:

Most 'disruption' of the status quo happens through unbundling. But most venture returns are realized through rebundling.

Understanding this one insight helps us make more nuanced predictions on where value will accumulate in a protocol-mediated ecosystem, and hence, who will win.

In the case of the ONDC ecosystem, the protocol enables unbundling.

However, a few players are uniquely positioned to rebundle and benefit most.

Before you dig into the juicy details, here’s another opportunity to share this further:

Flipkart and Amazon will emerge as dominant merchant services providers

As I shared above, online marketplaces win through

proprietary inventory (and the associated network effect) and

delivering fulfilment and returns through vertical integration across supply chain data from warehouse to home.

These are the two core sources of competitive advantage.

Those who don’t understand the second important source of competitive advantage are likely to conclude that when the proprietary inventory advantage gets commoditized by ONDC, the large marketplaces will lose.

On the contrary, when (and if) the first advantage of proprietary inventory gets commoditized, the second advantage of supply chain data becomes even more powerful.

Amazon and Flipkart are uniquely positioned to provide warehousing, fulfilment, and returns as-a-service to new players coming on board. This could well be the most profitable picks-and-shovels business in the ecosystem if ONDC adoption were to take off.

Seller onboarding and management is a key control point

This is one of the most important plays in the ecosystem. Companies like HUL are uniquely positioned to win here.

Since the onset of Covid, FMCG companies like HUL have invested heavily in onboarding their seller network online (on e-distribution networks) to reduce dependence on their slow and data-poor offline distributor network.

With ONDC, they now get the opportunity to plug these onboarded sellers into new distribution opportunities, drive greater growth for these sellers, and in turn, make them more committed to using HUL’s e-distribution and ordering services (like Shikhar).

This is yet another example of an incumbent uniquely positioned to win in the ONDC ecosystem.

Early stage startups and venture funds will largely foot the bill for product-market fit

As I explained in How to lose at Gen AI, certain market structures and profit pools overwhelmingly favour incumbent business models over startups:

We’ve seen an incumbent business model advantage play out in the shift to IoT.

Most incumbents - companies like Schneider, Johnson, and Honeywell - subsidized IoT services and bundled in the connected services with their existing profit pools where they charged for devices.

Clueless startups looking to capture value on connected services tried to subsidize their hardware and were left footing a huge manufacturing bill for subsidizing low quality hardware that took them nowhere.

Incumbents, instead, increased the value of their devices by bundling in subsidized connected services - a huge business model advantage.

Effectively, startups footed the experimentation and customer discovery bill while incumbents captured all the value.

Something similar will play out at scale in the ONDC ecosystem.

Buyer-side applications and services are not very lucrative when inventory data is open.

This is because audience acquisition is expensive and churn rates are high. The economics work (and only barely) for online marketplaces largely because they can retain these audiences through proprietary inventory, which they scale through network effects.

When inventory data is open, presentation of that data into a workflow is a fleeting advantage, not a sustainable one.

Incumbents with an audience will win without incurring the cost of innovation

Who, then, wins on the buyer side?

The players who will win on the buyer-side are players who

Already have a large audience (and not necessarily in commerce),

Currently serve that audience with profitable unit economics, and

Can now additionally sell relevant products and services to them.

Think of a media app which captures enough data about users to show them ads. It can now allow them to transact directly on ONDC and capture higher margins than through ads alone.

Startups (early stage) will largely foot the product-market fit bill. Once a use case is proven out, incumbents - anyone (including Series A/B/C startups) with a large audience and pre-existing positive unit economics - will swoop in to capture the value.

Early stage startups that rely only on the commerce flow most likely to lose

Early stage startups playing in the commerce flow (helping buy and sell) are the ones most likely to lose when the first core source of competitive advantage (proprietary inventory) is opened out and the second core source of competitive advantage (fulfilment and returns) is captured further by at-scale players.

Protocols are seductive in attracting startups looking to unbundle and niche down.

However, unless they rebundle along one of the lines above, they will fail to deliver venture returns.

And given the landscape above, early-stage startups will struggle to rebundle before an incumbent does.

Some early stage startups may still win, but largely outside the commerce flow

Yes, there are opportunities for startups to develop point solutions in the ecosystem and rebundle around that (using a playbook similar to the one I shared in How to win at Gen AI) but such point solutions will likely emerge in complements to the buying and selling process, rather than in the core commerce flow. For instance, financing and working capital provisioning - not directly in the commerce flow, but benefiting from the data that emerges out of commerce on the protocol - would be better placed to win.

A playbook for winning in a protocol-mediated ecosystem

How exactly do you win in the ONDC ecosystem… or for that matter, in any protocol-mediated ecosystem.

The answer lies in a combination of unbundling and rebundling - a playbook that I shared in How to win at Gen AI:

The playbook is written for Gen AI startups but the core concepts and the four step approach applies equally well to startups looking to play in open network ecosystems like ONDC.

Here’s the link again for a detailed read:

How to win at Generative AI

A couple of weeks back, I wrote a post on How to lose at Generative AI. Which raises the counter-question, how do you win at Generative AI? Of the many GenAI copycats emerging, which are the few that win? This post is about winning at Generative AI.

And while you’re at it, you should combine it with the other companion read…

Why your super-app strategy will (most likely) fail

Everyone wants to build a super-app. Yet, almost every super-app will fail. You don’t get to be a super-app just because you have a lot of users on your core app and you now decide to bundle multiple services into the same interface. You gain the right to be a super-app by

What next…

If this analysis flipped your mental models, or had you nodding all along, please feel free to write in and chat more.

Just respond to this email, connect on LinkedIn, or drop me a note at sangeet@platformthinkinglabs.com.

Help share this publication further!

Very well analysed. Having worked in e-commerce in India I can vouch that the coordination costs can b very high. I also see parallels to UHI though in healthcare there are no large incumbents. Would like to know your views on UHI.

What will be the scenario if a guy with lots of warehouse real estate and serving as a multi brand distribution hub were to expose his inventory as a fee based API subscription? Will that lead to standalone logistics players competing with non big players with an SCM in place? There is this DHL case that talks of intelligent supply chains https://dhl.lookbookhq.com/ao_thought-leadership_social-recommend/article_harnessing-the-predictive-supply-chain. Can ONDC create that for the average logistics provider such as VRL or Redbus (https://www.redbus.in/travels/yathra-logistics) by just exposing the data from (consented) inventory that goes through them. Will ONDC be a revolution for supply chains, by creating a "live catalog" (what is there where right now at what price and number) versus "promised catalog" (what is an idea or aspiration presented to you that can be delivered if you show the money).