Why your super-app strategy will (most likely) fail

Building competitive advantage in the attention economy

Everyone wants to build a super-app.

Yet, almost every super-app will fail.

You don’t get to be a super-app just because you have a lot of users on your core app and you now decide to bundle multiple services into the same interface.

You gain the right to be a super-app by

(1) gaining the primary right to customer relationship in a certain category (or in very rare cases, across categories), and

(2) gaining the right to mediate all other services (in that category) through your interface.

That may sound similar to pushing multiple services through an app interface.

But they are not the same thing!

And that’s why, most super-apps will fail to get anywhere close to the success of the ‘OG’ super-app that they all claim to emulate - WeChat.

In fact, there’s an entire continuum of super-app failure and most end up languishing across this continuum.

Let’s unpack this further!

The super-app fallacy

If I had a penny for every time I’ve heard a company claiming they will be the next super-app…

…well, I’d sure be carrying a lot of change!

Everyone claims to be building a super-app. Yet, all of these claims are victim to the same fallacy!

You don’t become a super-app by bundling multiple services into one single app interface.

You become a super-app by becoming the primary interface of choice for all these services (and more).

A small difference in words, a big difference in competitive advantage!

The first is classic industrial economy thinking. We own the supply (in this case, the many services) and hence the right to push them to the user.

The second is attention economy thinking. In an attention economy, the right to serve the user is scarce.

Pushing multiple services through an interface doesn’t make you a super-app, the right to primacy of user relationship makes you a super app.

Becoming the primary interface is no mean feat!

In an attention economy, control of the user interface is one of the strongest sources of competitive advantage!

It is also one of the most deeply contested value bottlenecks in any ecosystem, allowing you greater negotiation advantage over all other players. This is what makes a super-app play exciting!

Competitive advantage in the attention economy

As I’ve noted before in my post How to regulate Facebook and Google:

Business models are built around scarce and tradable resources.

Tradability affords value transfer and scarcity affords negotiation leverage in such transfer.

Attention is both scarce and tradable.

Attention is scarce - yes, because the sum total of human attention is a finite number.

But more important, with an abundance of content and interactions, our decision-making ability gets depleted, allowing our attention to be more manipulable as a resource.

Attention is also tradable. Sophisticated auction mechanisms, recommendation engines, and decision support systems trade our attention (and the attendant decision - which is already manipulable) to the highest bidder.

Your goal as a super-app is to manage both the scarcity and tradability of attention.

You gain the right to manage attention scarcity by gaining primacy of the user relationship through a core use case on which you have primacy of user relationship.

You gain the right to manage attention tradability by ensuring you own a key control point through which user attention may be traded with third parties.

Let’s unpack both these points further!

And if you’d like to read that piece on the attention economy further, here’s the full story for another tab:

Key concept #1: Primary demand vs secondary demand

Let’s start with the first key priority for winning in the attention economy:

Gaining primacy of the user relationship.

How do we make that happen?

Here, we need to make a distinction between primary demand and secondary demand.

A homebuyer has primary demand for a house. This primary demand generates secondary demand for mortgage.

In healthcare, the primary demand for cure and wellness creates secondary demand for pills and procedures.

The secondary demand is a means to an end, the primary demand is the end.

In an industrial economy, serving secondary demand was hugely profitable as long as you owned proprietary channels (e.g. bank branches, clinics etc.) and some form of regulatory moat (e.g. license to operate).

In an attention economy, where consumers are constantly connected and attention is both scarce and tradable, owning the primary demand is key.

The firms that own primary demand will eventually commoditize the ones that own secondary demand.

This is why banks want to move ‘beyond banking’ because they see profit pools shifting into the primary demand that ‘wraps around’ their product lines.

Back to super apps, to be successful as a super app, you need primacy of user relationship and that is best owned by owning a core use case in the primary demand.

You may be the largest seller of mortgages or health insurance but does the user engage primarily with you for their home buying decisions and their wellness management?

If not, you may not have the right to engage in a super-app play.

Key concept #2: Control point

Now that you have the right to primacy of user relationship, you need to determine whether all the services in the super-app will be served by you or by other third parties.

The key test here is the following:

Irrespective of who serves the services, your right to primacy of relationship should persist into these other services.

Essentially, if you’re serving a certain use case through your super-app, you can claim to be a super-app only if the user has no other app solving for the same use case on their phone. Absent that, you’re a glorified app bundle.

If you want to avoid being a glorified app bundle and get to super-app status, you need best-of-class apps on board.

But why would third party apps work through you?

Because you have primacy of user relationship… AND, crucially, a key control point. Integrating across primary user relationship and a key control point give you the right to act as a super-app on which third party apps sit.

Key components of super-app success

The right to manage attention scarcity and tradability gives you the right to play as a super-app.

Let’s translate that to product and business model requirements. The following are key components of super-app success.

High frequency core use case in primary demand, driving primacy of user engagement

First up, you need to have a market-leading, high frequency use case, preferably in the primary demand.

Your claims to building a super-app are likely hokum if you are not - at the very minimum - a market leader as an app already.

This use case should be high frequency, ideally daily or multiple times a day. That’s how you maintain primacy of user relationship.

Ideally, this core use case should be in the primary demand. You could also play in the secondary demand only as long as you’re enabling a market-leading, high frequency use case, but your super-app potential is a lot weaker as I’ll demonstrate in the subsequent sections.

Market leading payment provider of choice

With the above sorted, you ideally want to combine your market-leading primary use case with a market-leading payment capability.

All super-apps eventually need to own the payments layer.

WeChat combines market-leading, primary demand use case (communication) with market-leading payments capability.

Transportation players like Grab and Careem start with transportation as a high frequency primary demand use case and move backwards into owning the payments wallet.

Workflow or business model advantage to increase scope

Additionally, your claim to super-app status is strengthened if you own some form of workflow or business model advantage.

WeChat owns the communication layer, which grants it a workflow advantage, allowing other apps to sit within that communication interface. Hence, it owns the right to increase scope of services.

Ride-hailing apps extend to delivery and other logistics services, not just through owning a common payments layer, but through owning business model capabilities (driver supply, routing capabilities, traffic data etc.) which allow them to expand to other use cases and deliver a far superior expense than someone solely serving that use case. Local services also require city-level marketing spends which are best cross-leverage across multiple services than focused on a single one. As I will shortly demonstrate, these ‘super-app’ plays again have severe limitations but this business model advantage provides some competitive advantage over new players starting off in a single category.

Scale and scope of data capture

Finally, in order to maintain primacy of user relationship (go deep) AND mediate multiple services (go wide), you need to ensure that you constantly increase both scale and scope of data capture. This creates a nice flywheel effect. Greater scope of data capture allows you to add more services, which in turn, creates greater engagement and depth of data capture, which in turn, strengthens your super-app position to keep expanding scope.

Super-app plays - Three degrees of defensibility

Not all super-app attempts are created equal.

There are primarily three categories of super-app plays:

Vertical-agnostic primary-demand super-apps

These are, by far, the most successful super-app plays, and fittingly, the ‘OG’ super-app play - the play that created the category and this global frenzy to build a super-app.

These plays (I use the plural even though WeChat is the only example truly deserving of this spot) are use-case agnostic, allowing them to absorb and bundle a large scope of apps.

They win because of

(1) access to a key horizontal workflow (in the case of WeChat, the primary communication interface), and vertically integrate that with

(2) the dominant payments capability.

As I explained in last week’s article on Gen AI:

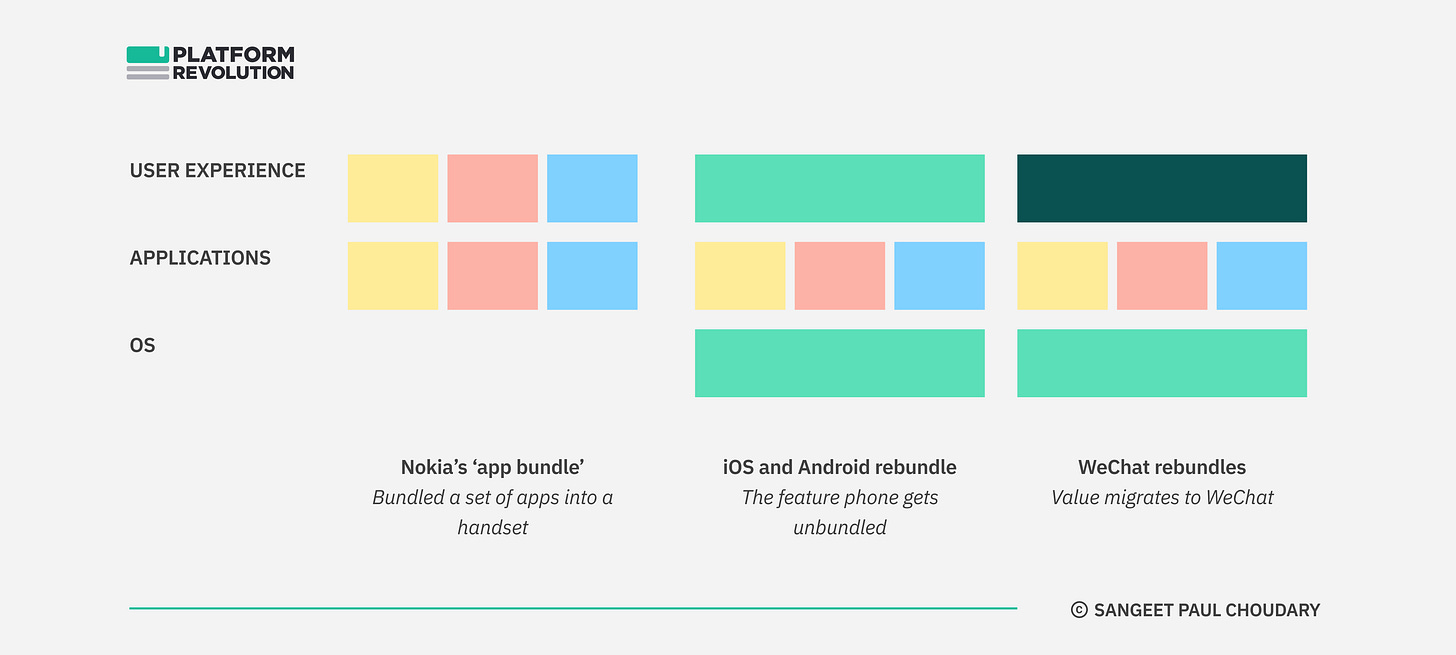

WeChat started as an individual app with vertical advantage in gaming and communication. However, it moved on to use its dominance in communication to establish primacy of user relationship as the default communication channel. It then integrated communication with payments to control the two most important horizontal capabilities that allowed it to establish a new layer on top of the underlying OS.

Vertical-specific primary-demand super-apps

These are the WeChat wannabes who’ve demonstrated some level of narrow success within a vertical. Local services players like Grab, GoTo, and Careem are great examples.

All of these players follow a common path.

They start with a daily vertical use case in the primary demand - transportation.

They use this high frequency use case to gain access to the payments capability.

They then use payments and other local advantages to expand into other local services, typically food delivery, cleaning services etc.

As you’d imagine, there are limits to extending scope of services beyond the vertical. This is both a disadvantage (in limiting super-app scope) and an advantage (if vertical focus comes with business model advantages in the vertical).

Vertical-agnostic secondary-demand super-apps

A third category of players are fintechs - typically payment providers - which wrap additional services around a core payments capability.

These plays benefit from horizontality of payments but may find it challenging to move from the secondary demand layer of payments into the primary demand of the many use cases into which payments can be embedded.

Arguably, these plays are more successful when targeting small businesses. For small businesses, payments and money management - even though secondary demand - are core to day-to-day functioning, and hence, accord the right to primacy of user relationship that may be more elusive for a payments player looking to target the consumer.

And finally, we encounter the graveyard of wannabes. The many companies that claim to be building a super-app but are merely bundling multiple services into a single interface.

If anything, this is a significant step backward. At the dawn of smartphone app development, app developers tried to build apps the way they did websites - with multiple tabs and multiple use cases. Very soon, it became apparent that mobile apps would be ‘thin sliver’ and highly unbundled.

Today’s super-app wannabes who lack the right to play as super-apps are merely taking us back to the failures of 2007-09 when bloated apps failed to gain traction and wondered why they were failing.

Success with a super-app strategy

Back to the title of this article.

Here’s why your super-app strategy will most likely fail!

Your super-app strategy will (almost certainly) fail if you’ve told your investors that you’re going to be the next WeChat!

As already demonstrated above, there are three vastly different categories of super-apps and three different levels of super-app success.

1. WeChat

(vertical-agnostic, primary-demand)

When it comes to super-app success, WeChat is in a category all its own.

As I explained in last week’s article on winning at Gen AI:

At one point, WeChat had such primacy of the user relationship that new OS updates from Apple and Google had no impact on the user experience unless WeChat implemented those updates into its UX.

WeChat is the much-quoted epitome of super-app success. It succeeded in becoming an alternate layer for apps at which apps operated, relegating the mobile OS layer to the background, and effectively commoditizing it.

WeChat established itself as the dominant interface for app-bundling and usage.

You could still build some sort of a super-app, but you will (almost certainly) not achieved the dominance and defensibility that WeChat did.

This brings us to two other super-app plays, which are often spoken of in the same breath but are far less dominant or defensible.

2. Payment super-apps

(vertical-agnostic, secondary-demand)

Most payment players looking to build super-apps are merely ‘wrapping’ primary demand use cases (typically e-commerce) around their secondary demand advantage in payments.

Success, here, is relatively modest. Becoming a super-app only helps you defend your payments business by driving greater usage of the underlying payments capability through wrapping primary use cases around its embedded secondary capability.

3. Local services super-apps

(vertical-specific, primary-demand)

Success continues to be relatively modest when you move into local services super-apps. Companies like Grab, GoTo, Careem claim to be building WeChat-like super apps.

No, they aren’t getting anywhere close in terms of dominance and/or defensibility. They are merely expanding customer share of wallet within their category.

Local services is a category filled with such plays.

Players here start with transportation, use that as a way to get access to consumer payments, and then extend horizontally (but within limits) using the payments advantage to spillover into other local verticals like food delivery, home cleaning services etc.

In summary, you’re going to end up with a vastly different level of ‘success’ depending on which type of super-app you’re building. This graph summarizes what outcomes you could look to expect in each category of play

You’re not going to build the next WeChat!

Crucially, it is important to note that WeChat was not just the dominant communication workflow that also happened to do payments nor the dominant payments player that moved into workflow.

WeChat’s unique advantage lies in the fact that it was independently the dominant communication workflow as well as the dominant payments player (with some ongoing tug of war for dominance with Alipay). Yes, it leveraged its dominance in the former to build dominance in the latter. But it remains the dominant player at both layers in the Chinese market and successfully integrates across the two in its super-app play.

No other player comes close.

Local service super-app wannabes like Grab and GoTo gain access to the payments layer but are never the dominant payments player in their market (except for the narrow set of use cases related to local services). On the other hand, payment player like PayPal and PayTM never quite gain dominance in the primary demand and remain a payments player that happens to do e-commerce. In all fairness, they never get to establishing the key control point that makes a super-app successful.

The test of WeChat-like success at the super-app play

We’ve talked about different levels of success at building super-apps. Clearly, success ranges from glorified app bundles at one end to WeChat-like dominance at the other.

So what’s the test of WeChat-like success at the super-app play?

I believe there are two conditions that determine whether you’re going to be a true super-app WeChat style.

First, you need to have true primacy of the user relationship. Essentially, if you’re a vertical play, you should own all use cases within that vertical. The user should not have any other app in that vertical on their phone. For instance, you’re really successful as a local services super-app if the user no longer has any other app on their phone for local services. Absent that, you’re yet another glorified app bundle. Nothing wrong with that. But it’s not a super-app.

Second, and this is where it gets really interesting, you should be the new home for apps. If you’re truly successful at the super-app play, users should be interacting with apps through your interface rather than anywhere else.

This is the true test of success with a super-app play. As I explained in How to win at Generative AI:

Users spent most of their time inside WeChat. This enabled WeChat to rebundle the apps at a layer above the OS layer. Apps for e-commerce, gaming, media etc. could now sit inside WeChat. Users never left the WeChat workflow because of its all-in-one connective workflow of communication and payments across apps.

At one point, WeChat had such primacy of the user relationship that new OS updates from Apple and Google had no impact on the user experience unless WeChat implemented those updates into its UX.

The first condition above is a minimum requirement to establish primacy of relationship with the user.

The second condition above also establishes that your control point is strong enough for you to be the default interface for third party-apps.

Thinking beyond super-apps

A super-app is one of many versions of setting up a competitive position in a digital ecosystem. All super-app ambitions start from an underlying desire to seat yourself at the centre of the ecosystem.

But defaulting to super-apps as a solution does not make sense unless you clearly understand your ecosystem and the unique control points you can claim access to within it.

To gain the strongest position in the ecosystem, a far more systemic approach is to map out your ecosystem and identify the key business models within it which provide you greatest strategic leverage and where you have a right to execute through ownership of the key control points.

If you’d like to discuss this further, please write in to tripta@platformthinkinglabs.com to request a copy of our advisory kit.

Great Article!!

Don't you think that one of the main reason of Wechat's success is due to its mini-apps platform (somewhat different to super apps in terms of engineering, scalability, control etc etc).