The vibe coding paradox

How to build competitive advantage when execution is cheap

The economics of abundance are a funny thing!

With the fall of the Berlin Wall, much of Eastern Europe experienced a rapid shift from censorship to expression. What followed alongside the political transformation was an explosion in media as previously underground pamphlets became national newspapers and long-suppressed ideas started showing up on public forums, free from restrictions.

The barriers to expression had fallen. However, the infrastructure for navigating this new abundance, primarily editorial judgment and cultural filters, had not yet formed.

Václav Havel, a playwright and dissident who eventually turned president, had spent years crafting works that had gotten him behind bars. But when finally given the platform to speak freely, he strangely exercised restraint despite the political platform he was given.

Havel figured that when expression was cheap, capturing attention became expensive. In such a system, the actor who speaks less but with greater precision holds power.

Havel remains one of the few leaders from that period remembered for defining its moral and cultural terms. While many post-communist leaders receded into political obscurity, Havel remains internationally recognized as a moral philosopher-statesman. Biographer Michael Žantovský describes Havel’s approach to media as intentional absence.

Havel stands out. In fact, in an essay that came out the other end of going down the rabbit hole of understanding Hayao Miyazaki’s approach to art and the Japanese pursuit of aesthetic, Havel’s story stood out as the one to explain today’s vibe coding paradox.

The vibe coding paradox

Havel lived through a shift towards abundance driven by political forces. Today, something similar is playing out though the forces are technological.

Building a functioning app took days, perhaps months of coding. Frictions of time, skill, and cost built into that process served to filter what got made.

With AI, those frictions go away. Prototypes can be built in an afternoon with a good set of prompts. Every form of knowledge work has seen some form of acceleration.

Everyone can ship more, and more often.

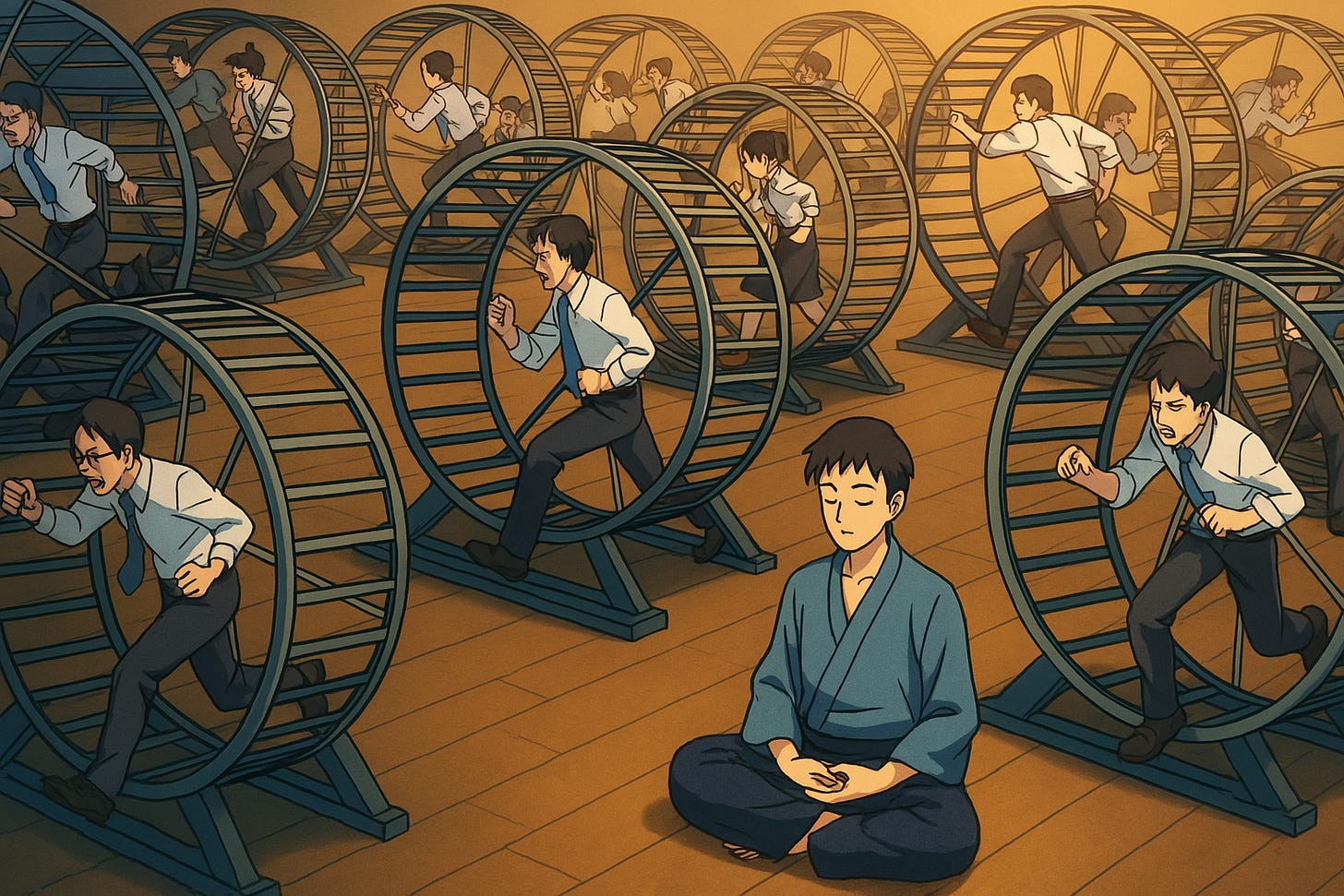

Most people, sensing the new speed, get onto a productivity treadmill, constantly producing. Developers brag about how Claude or Cursor has replaced Netflix as their late-night addiction.

What looks like productivity and faster work

is really the commoditization of execution.

Tasks that once conferred competitive advantage through difficulty or skill are now widely replicable.

But as execution becomes easier, the value of any individual action goes down, just as it did in Vaclav’s post-Soviet Europe.

This brings us to what I call The Vibe Coding Paradox. The more frictionless execution becomes, the more it loses value.

Value shifts to discernment - knowing what to produce.

But instead of adjusting to this shift, most people double down on output. They respond to new capability with more action, not better intention.

If execution is no longer scarce, the thinking goes, then the only way to stand out is to do more of it. The result is a kind of productivity treadmill: lots of movement, little meaning.

This logic is, of course, flawed and self-defeating. When output becomes frictionless, quantity can become a liability.

The more we produce without purpose, the harder it becomes for anyone to distinguish the meaningful amongst the noise.

We create more than ever, but it doesn’t stick. It doesn’t shape us, or others.

The real scarcity shifts from doing to choosing what to do. Discernment, not productivity, becomes the differentiator.

Too much content, too little attention

We’ve seen this before. With the rise of social media, everyone became a content creator, but only a few mastered the sort of attention that compounds to long term trust.

Most creators chased volume. But with more content, attention became the limiting factor. Brands that really succeeded rose not through content, but through narrative and taste.

The same pattern had played out a century earlier. Industrialization had transformed manufacturing. What once required artisanal labor could now be replicated at scale. But this didn’t make every product valuable. It simply shifted the point of differentiation. As Henry Ford’s assembly line made cars affordable, it was companies like General Motors that figured out how to win through brand, design, and segmentation. As production scaled, value migrated from the factory floor to the design studio and marketing department.

Abundance reshapes the scarcity equation.

It doesn’t eliminate scarcity. It shifts it.

Execution is only valuable when it’s scarce, hard, or differentiated.

Trust and attention confer value on our creations.

The problem - and the reason the Vibe Coding Paradox comes up - is because we live in an age where it is possible to hack our way to attention without having to do the hard work needed to build trust.

With that, we misunderstand attention as value. But without trust, it really isn’t.

In an age of mass production, curation and taste matter more.

AI productivity is now creating a world where everyone can execute, but only a few will figure out what’s worth executing.

Innovation theatre and the productivity paradox

The vibe-anything trap is that it convinces you that you should do more just because you now can. Productivity becomes a treadmill with no destination.

But the paradox of abundance is that what used to signal effort now means nothing.

Productivity is no longer progress, it’s just movement without direction.

Something similar happens with the innovation theatre observed in organizations looking to respond to disruption.

When the ‘tools’ and ‘methods’ of innovation become abundant - when everyone can feel smart by sticking post-its to a wall - good strategy (which requires deep thinking using first principles) takes a backseat and aimless experimentation and prototyping takes over.

This problem is especially magnified with canvases that are increasingly used for solutioning. Filling a generic canvas or framework makes the hard part of strategy seem easy. In reality, it is anything but strategy. It distracts participants in the process away from first principles. It provides the semblance of structure in the midst of structural uncertainty. It seduces you into thinking that if you only fill out the boxes out there, you’ve successfully answered the hard question of what should be done.

This is bound to increase, not decrease, with the new AI tools at our disposal. Yes, you can iterate and ideate more with faster prototypes. You can test ideas faster than ever. But without good strategy, you can also end up in cycles of chasing local optima - constantly climbing stupid, small hills that don’t need to be conquered.

This is the trap of the learning organization. While learning is critical in order to sense and respond to uncertainty, institutionalising a process out of it - without strategy that informs it and is informed by it - is simply another example of the vibe-coding paradox.

What’s valuable?

So in the midst of abundance, what is valuable?

Value migrates to those who choose carefully and act selectively.

To the three core capacities that define advantage in an age of abundance:

Meaningful restraint

Careful craft

Developed taste

Eventually, in a world of cheap and abundant answers, good questions matter the most:

Let’s look at each of these in turn:

Meaningful restraint

What do you do if the skill you used to compete on suddenly gets commoditized?

When your previous edge becomes abundantly available, you can’t just continue playing more of the same old game. You need to change your game.

Abundance kills advantage, unless you shift the game.

The Japanese brand UNIQLO’s response to fast fashion is an interesting example.

When brands like Zara and H&M started launching new styles weekly in a game where clothing had become abundant, and disposable, most players responded by chasing faster design cycles.

UNIQLO chose to double down on science instead. It changed the game it was playing.

UNIQLO invested in creating proprietary fabrics that solved real, everyday problems. Its thermal-wear, made from micro-acrylic fibers, generate and retain heat using body moisture to create warmth without adding layers. Anyone could make a black turtleneck. But only UNIQLO could make one that retains body heat, stretches perfectly, feels like second skin - all while costing under $20.

In high-execution environments, restraint helps you think carefully about how the playing field is changing. If you keep playing the old game - only faster - there is no way you can step back to learn the new rules.

Restraint helps you step away from a game that isn’t worth winning anymore.

The ability to hold back may become the most underappreciated form of leverage we have.

Yet, as the past fifteen years of social media demonstrate, most of us will head in the opposite direction.

Careful craft

When everyone can build, scarcity shifts from product to meaning.

If everyone can produce and flood the market with products (whether code or writing or spammy LinkedIn invites), our limited attention craves meaningful narrative.

The Japanese beauty brand Shiseido had a century-long head start making beauty products. But by the 2010s, cosmetics were everywhere. Cosmetic formulations had become commoditized. Korean beauty (K-beauty) and global indie brands were churning out high-quality products at speed.

So it stopped talking about ingredients and started investing in storytelling. Its products now came with heritage and rituals.

Shiseido’s skincare lines were now positioned as daily rituals of self-care. The packaging was inspired by lacquerware, and campaign visuals evoked calm and stillness.

The Shiseido Corporate Museum in Kakegawa and the Ginza flagship art space became storytelling platforms, embedding the brand further in a narrative of Japanese modernity and design evolution.

They relocated value from product to narrative.

Abundance simply relocates scarcity.

Careful craft, in this sense, creates meaning around your creations. But it also creates meaning for you in your work. Excessive execution can make us feel disconnected from our work. The friction involved in creation helped us connect with what we created. As creations become easier to churn out, meaning has to be brought in through narrative.

In a high-execution world, where tools threaten to abstract us from our own creations, careful craft keeps the feedback loop tight. It trains judgment. It builds taste.

Careful craft holds a kind of asymmetric power. When everything speeds up surface-level cycles, the few who know how to go deep, will create something that stands out from the rest.

Developed taste

Taste is a fuzzy concept.

But you can see it in the work of George Nakashima, the Japanese-American woodworker whose tables and chairs now sit in museums as often as in homes. Nakashima selected slabs of wood for their quirks and imperfections. Mass manufacturing would reject the same slabs for the knots and cracks, counting them as flaws. Nakashima had developed taste to figure which of those could be turned into art.

You can’t shortcut your way to taste. It’s tacit knowledge, something you can’t easily codify or explain.

Tools can help you execute faster, but they lack taste.

Taste is an interesting form of ‘knowledge work’ that remains immune to AI. And it becomes especially valuable when execution is easy, because it’s the only reliable way to cut through commoditized outputs. If anyone can generate a hundred options, taste helps choose the one option that makes sense to pursue.

In a high-execution world, taste attracts attention and cuts through the noise.

Buy Reshuffle

This post is based on ideas from my book Reshuffle - now available on Amazon. For a deep-dive, get your copy today!

Pre-orders are Kindle only.

Hardcover, paperback, and audiobook versions will be available at launch.

Stop blitzscaling, start tinkering instead

In the age of abundant execution, tinkering moves from a weekend side-hustle to becoming your central advantage in the constant pursuit of career reinvention.

Blitzscaling tries to scale before the system knows what it’s scaling. Tinkering starts small and adjusts constantly, listening for what matters and what doesn’t.

Tinkering develops taste!

It values curiosity over completion. When everyone can move fast, it’s not how fast you move, but whether you’re moving in a direction that matters.

Tinkerers thrive in abundance because they’re not locked into the logic of scale. They prototype, remix, adapt. Ironically, the ones who tinker well, also often end up scaling with more leverage and less waste.

When value no longer lies in doing more, but in discovering what’s worth doing, tinkering provides a path to strategy.

So stop blitzscaling. Start paying attention. Start tinkering.

But what do we do with all this taste?

So does scale not matter anymore?

Do we all now become careful craftsmen exercising meaningful restraint and developing taste?

We tend to think of taste as subjective. Elusive. The opposite of scale. Something you either have or don’t. A soft power that resists systemization.

What we’re going to look at now is probably the least understood and the most important lesson to developing strategy in an age of abundance.

Most people misunderstand taste. They treat taste as a signal of personal flair - something very Marie Kondo - what resonates, how you decorate.

But the real power of taste isn’t in what you show. It’s in what you disallow.

Taste is a superpower when expressed through systems design.

The case of the reluctant retailer

By the 1990s, global manufacturing had shifted the economics of consumer goods. Production capacity was no longer a constraint. Factories in East and Southeast Asia could deliver near-limitless variations of everyday items at increasingly lower marginal cost.

This abundance led to a shift in competitive dynamics. Companies could no longer differentiate purely on access to production or even on design quality. As variation became easy to generate, firms began to optimize for breadth, with more SKUs, more colors, more features.

The logic was that more choice would capture more demand. But this created a new problem: too much variation began to confuse customers. Consumers had more options than ever, but less confidence about what to choose.

The Japanese brand Muji emerged in response to these excesses of branding.

Short for Mujirushi Ryohin (no-brand quality goods), Muji creates narrative and meaning across its products through minimalism. Its products - pens, notebooks, furniture, household items - feature no visual embellishments. To the casual observer, it may look like an aesthetic decision: a minimalist style that stands in contrast to the visual clutter of the time.

Muji has meaningful restraint. It has careful craft.

Muji has taste!

But if you stopped right there, you would miss what Muji is really doing - creating a system to counter what we’ve called here the vibe-coding paradox.

Muji isn’t simply expressing a design sensibility.

It is creating a system of constraints into its operating model, all structured around its design choices.

First, the absence of brand names - while distinctive from the branded noise that filled retail shelves - also required Muji to build direct sourcing relationships with manufacturers willing to produce without attribution. This resulted in a private-label supply chain that could maintain quality while eliminating the markup and complexity associated with branded goods.

By refusing to compete on logos, Muji forced itself to compete on systems.

Next, its plain packaging, standardized across categories with uniform font usage and precise dimensions, wasn’t just for visual effect. That one choice simplified procurement, reduced production costs, and ensured visual consistency across the store. The store layout itself mirrors the editorial logic of a well-curated magazine: categories flow logically into each other, and shelf space is treated more with the aesthetics of interior design than as advertising real estate.

Muji’s meaningful restraint has given it a unique supply chain design that other loud brands simply couldn’t copy.

Muji inverted a core assumption of retail economics. Most companies attempt to differentiate through product proliferation or marketing. Muji narrowed its product range and removed promotional cues. In doing so, it increased the cognitive ease of consumption.

It created meaning through narrative. Consumers didn’t need to evaluate every individual product and the brand easily spilled over across unrelated categories.

Muji’s taste was encoded as operational rules that shaped sourcing, design, packaging, and merchandising. And because those decisions were systematized, the brand could scale without diluting its identity.

Stores in Tokyo, London, and New York carry different products depending on local needs, but the spatial and aesthetic grammar remains unmistakably Muji.

Muji’s model essentially created a form of soft integration; not full vertical control like a traditional manufacturer, but enough ownership of upstream and downstream decisions to enforce consistency.

The supply chain became an extension of the brand, and vice versa.

This made Muji unusually resilient to the pricing pressures of commoditized categories. Muji’s margin is paradoxical - correlated with some of the most powerful brands, but built not through brand markup, but through system efficiency and customer trust.

Taste, in this context, is not simply a matter of surface-level design. It is a design choice encoded across operations, supply chain logic, and the firm’s decision making heuristics.

In a world where anyone can produce a product,

competitive advantage is created through

taste and narrative, crafted through restraint,

and scaled through a system of complementary assets

Coherence is system-level taste

For creators, founders, and designers navigating a world where execution is cheap, the temptation is always to move fast.

But as speed becomes abundant, it stops being strategic.

This is where taste, as a strategic asset, demands a different approach. It’s no longer enough to define your taste as a set of personal preferences or abstract principles. In environments shaped by abundant execution, taste has to become operational. It must be codified into decisions, embedded into workflows, enforced through constraints; not by micromanagement, but by structure.

In a world of infinite execution, the systems that endure are not the fastest. They’re the most coherent.

Coherence is what lets you move without losing identity. It ensures that what you scale still carries the logic of what made it meaningful in the first place.

Muji illustrates that coherence is not achieved through central control alone, but through a well-defined system of constraints that narrow decision-making across the organization. These constraints reduce unnecessary variation, align upstream and downstream activities, and make the customer experience more predictable.

More importantly, they create a form of defensibility. In markets where production is commoditized and aesthetic variation is infinite, the firms that succeed are those that can impose limits on themselves in ways that reinforce clarity for the user. Coherence, when structured into the system, becomes a strategic asset.

What matters is not scale, but coherence.

Coherence is taste structured across the entire system.

Vibe-drawing vs. Studio Ghibli

If you hadn’t heard of Studio Ghibli before, you’ve probably heard of it now with OpenAI making that previously scarce form of execution suddenly widely accessible.

The idea of counterfeiting someone’s signature style and making it widely available has a lot of ethical issues attached. But what’s more relevant to our point here is looking back at the conditions under which Studio Ghibli made its mark on the world.

In the late 1990s, anime exploded into a global phenomenon, powered by international syndication and high-volume serialization. Studios raced to capture global attention through spin-offs and sequels.

Hayao Miyazaki - already a legendary figure - could have transformed Studio Ghibli into a content powerhouse, capitalising on this explosion.

Instead, he insisted on keeping the studio small and independent. He drew thousands of frames by hand, the opposite of today’s obsession with blitzscaling. His team sometimes redrew entire scenes late in the process, just to get the mood right. To ensure there was coherence.

Miyazaki knew that once speed of execution became the organizing logic of the studio, the coherence achieved through evocative design and aesthetic integrity would be lost.

All of this shows through in Spirited Away, a film that became the highest-grossing movie in Japanese history at the time. While much of the mass-produced anime of the era faded away, Spirited Away remains a cultural landmark.

Miyazaki’s restraint was a strategic response to abundance. When industrial scale pushed the industry toward quantity, he doubled down on coherence and taste.

And today’s Ghibli-style imitations flooding the internet sort of prove the point - they look cool but lack what truly matters - the meaning and coherence of Spirited Away.

This post is based on ideas from my book Reshuffle - now available on Amazon. For a deep-dive, get your copy today!

It reminds me of an exchange from Mad Men between Peggy and Don.

"Peggy Olson: Sex sells.

Don Draper: Says who?

Just so you know, the people who talk that way think that monkeys can do this. They take all this monkey crap and just stick it in a briefcase completely unaware that their success depends on something more than their shoeshine.

YOU are the product. You - FEELING something.

That's what sells. Not them. Not sex.

They can't do what we do, and they hate us for it."

This piece nails the dilemma of abundant execution: when everyone can produce, only a few will matter. But what he calls 'taste,' I call trustworthy coherence. This isn’t just about aesthetics or strategic restraint. It's about meaning, consequence, and accountability.

Platforms now churn out infinite “vibes.” What’s scarce? Not code. Not content. Credibility. Alignment. Narrative integrity.

Taste without trust is branding. Trust with structured coherence? That is power.

Miyazaki’s restraint wasn’t just artistic. It was moral. Muji’s minimalism wasn’t style. It was operationalized epistemology. We are no longer crafting products. We are shaping systems of belief.

In a world where every answer is cheap, the real work, the dangerous, sacred work, is asking questions that matter. Then, having the discipline to build slowly, visibly, and trustworthily until something true remains.