Why offline retailers fail at online marketplaces

The seductive lies of network effects - Part 1

Once upon a time, retailers invested in large swathes of land, arranged aisles with the choicest of products, and built a fortune serving suburbia.

Then Amazon happened!

Over the past two decades, as Amazon has increasingly eaten retail with transaction economics that don’t make sense, retailers have constantly looked for ways to beat Amazon at its game.

Or, at least, get a hang of playing that game in the first place.

During this time, a range of consultants, tool providers, and transformation experts emerged with one common advice:

“In the age of Amazon, offline retailers need to become online marketplaces. Benefit from infinite shelf space and scale with network effects.”

Sounds enticing!

And yet, most offline retailers fail at running online marketplaces.

The promise of network effects comes with seductive lies that sound true but aren't quite.

This is the first of a series of posts unpacking the seductive lies of network effects.

Let’s dig into this one!

The lazy logic of distribution advantage

Here’s the network effect playbook that consultants and marketplace Saas providers repeatedly offer retailers:

You’ve got a huge customer base but you don’t carry everything they want

Move online, get infinite shelf space, and open out to third party merchants

You now play across many more categories with this open marketplace model and can increase share of customer wallet

But here’s the real kicker, you now scale through network effects: the more merchants you bring on board, the more value for consumers, the more consumers spend, the more merchants want to come in

Sit back and let the network effect grow your marketplace sales

Sounds easy!

But this almost never plays out as promised here.

This line of reasoning assumes that you can use your access to customers to kickstart a network effects flywheel, which will eventually scale your access to customers even further.

To understand the flaw with this reasoning, let’s step back and look at how this plays out for Amazon.

The half-truth of the Amazon flywheel

What is the real source of competitive edge in online commerce?

There is a common myth that the sole reason e-commerce marketplaces win is the network effect created through inventory aggregation.

The larger the scale and scope of inventory, the greater the choice for consumers, the higher the network effect.

The famous Amazon flywheel visual perpetuates this further.

This begs the question - Why can’t Walmart, Target, Macy’s and every other retailer run the same flywheel?

They’ve got the selection, they can operate a great cost structure, they can even bring third party merchants onboard.

What gives?

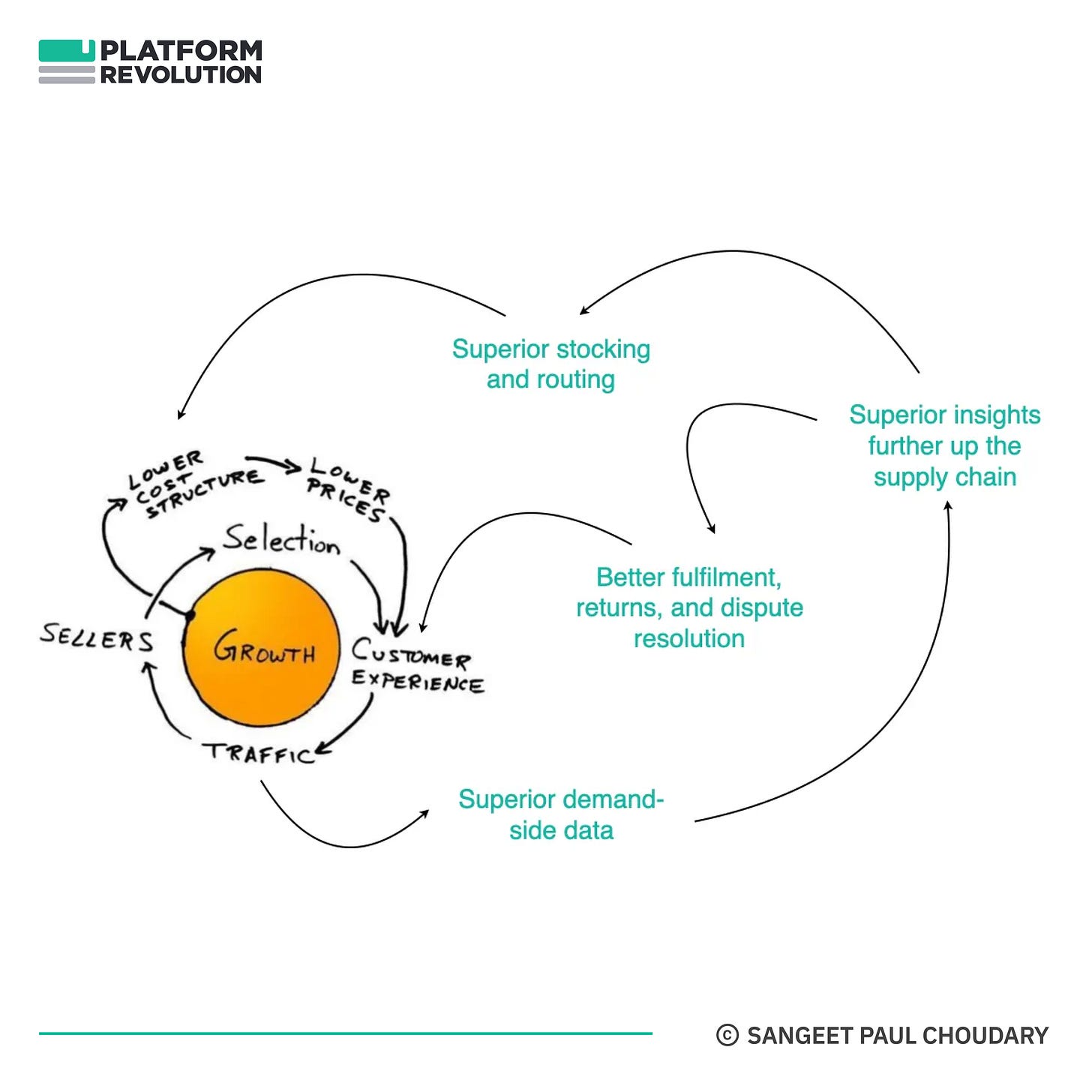

This flywheel tells only one half of the story.

Will the real Amazon flywheel please stand up?

The bigger reason offline retailers fail at online commerce is their inability to profitably manage fulfilment, returns, and dispute resolution. These are the three factors that determine transaction economics.

First, managing fulfilment to the home requires management of 70 different use cases (leave it with my neighbour, use my smart lock, don’t play with my dog, the works…) as compared to store-based fulfilment.

This involves a fundamentally different supply chain.

Offline retailers struggle because their distribution centres and supply chains are geared towards in-store fulfilment, which involves far fewer - and more static - use cases.

Serving

40 stores

with predictable assortment needs

through 2-3 distribution centers

is orders of magnitude less complex than serving

millions of consumer homes

with unpredictable and ever-changing buying behavior

and expectations of same-day or two-day delivery

Second, fulfilment, returns, and dispute resolution cannot be delivered at scale without supply chain data gathered through vertical integration from the warehouse to the home.

None of the traditional retailers have supply chains geared towards this.

The real reason offline retailers can’t even get into the playing field - ironically - isn’t so much the network effect.

It is the fact that they have far less vertical integration across supply chain data.

In particular, they lack demand-side data integration.

Ironic - given that we’ve spent so much time crafting the narrative that offline retailers would win if only they could move from being a retailer to being a marketplace.

Selection and choice (marketplace benefits) are critical to consumer experience, but no less critical are fulfilment, returns, and dispute resolution.

And that brings us to the real Amazon flywheel - the one that no one tells you about. Because the half-flywheel looks insightful enough to go viral.

Why demand-side data integration matters

Now that you’ve shared this article further, let’s get back to the flywheel for a bit.

The crucial component here is demand-side data.

Demand-side data informs the entire supply chain.

Why is demand-side data integration so important to a successful supply chain play?

To understand this, let’s look at another online commerce player that defeated an offline incumbent through the sheer brilliance of its supply chain: Netflix.

If 2012 feels like ancient history, it’s worth calling out at this point that long before Netflix became the online streaming giant that it is today, it was a DVD rental startup delivering DVDs to doorsteps across the US. Blockbuster - the appropriately named incumbent - was the 800 pound gorilla that no one could unseat.

And yet Netflix did, in record quick time.

I’ve written about this in an earlier post:

You could argue that there were many things that drove Netflix’s success in the DVD rental business. But the one thing that Blockbuster could never compete with was the integration of demand-side queuing data (users would add movies that they wanted to watch next into a queue) with a national-scale logistics system. All this queueing data aggregated at a national scale informed Netflix on upcoming demand for DVDs across the country.

Blockbuster could only serve users based on DVD inventory available at a local store. This resulted in:

1) low availability of some titles ( local demand > local supply), and

2) low utilization of other titles (local supply > local demand).

Netflix, on the other hand, could move DVDs to different parts of the US based on where users were queueing those titles. This resulted in higher availability while also having fewer titles idle at any point.

Queueing data improved stocking and resulted in higher utilization and higher availability. It allowed Netflix to serve local demand using national-scale inventory.

Traditional supply chains need to manage the trade-off between utilization and availability.

But the ability to predict demand solves this trade-off and informs stocking and logistics.

This is why offline retailers struggle despite access to a customer base.

The seductive flywheel of Netflix

In other words, this is the seductive flywheel that you would normally associate with Netflix’s DVD business:

But this doesn’t explain why the incumbent loses.

Blockbuster could do all this much better… and more…

That’s because the full flywheel looks something closer to this.

Notice the red arrows that I’ve thrown in there? Those are the two arrows that make all the difference.

One arrow ensures high availability of DVDs locally, the other arrow ensures high utilization of DVDs at national scale.

There was no way for Blockbuster to compete with Netflix within the framework of local inventory - local fulfilment. Netflix fundamentally changed that framework.

And yet, you could run an entire class on network effects or go viral on YouTube if you only shared the first flywheel.

Why are these incorrect flywheels so seductive?

Because people want simple answers. And a flywheel that brings together obvious components is easy to relate to. The role of demand-side data in informing supply chain flexibility is non-obvious and more difficult to fully appreciate.

The economics of the world’s most successful membership program

Well, that worked for Netflix… but how does it work for Amazon? Amazon doesn’t really have a queueing function.

Amazon has something better.

Amazon runs the world’s most successful membership program. It’s called Amazon Prime. It’s a lot more effective than the queueing function.

Prime provides demand-side data to the supply chain. Prime users spend much higher than regular users. More importantly, they browse Amazon much more often than they buy and keep adding items to cart and saving them for later, signals that work in a way very similar to Netflix’s movie queueing function and help Amazon determine demand patterns at national scale.

Prime is uniquely defensible for three reasons:

Offering 2-day delivery is non-trivial. It requires a warehousing footprint informed by data on where users are shopping from.

Prime delivers high-margin profit to the balance sheet (in the form of membership fees), all of which is reinvested in expanding the warehousing footprint. This creates a virtuous cycle.

Prime’s value constantly increases as a bundle. It is no longer simply about 2-day deliveries. It also bundles movies and music. JP Morgan estimates that the value users get from Amazon Prime is worth at least 6 times what it costs.

Any retailer can set up an online marketplace and aggregate third party inventory. But they can’t set up a program where they offer 2-day delivery to users for a membership fee.

Prime is the widely visible, yet insufficiently understood, ingredient in Amazon’s success as a marketplace.

Fulfilment to the digitized doorstep

Amazon is constantly looking to improve its demand-side data footprint. All of this essentially translates to one goal: Digitizing not just your buying behavior and intent but also your doorstep and sidewalk.

Amazon acquired security device manufacturer Ring to digitize physical interactions at the doorstep. Beyond the doorstep, Amazon has far more ambitious plans for digitizing the last mile. Amazon Sidewalk creates a neighbourhood-level mesh network enabling compatible cameras, smart locks, motion sensors etc to be connected. Amazon Ring Car Cam extends its security footprint into the car.

Security is an entry point use case for Amazon but the end game here is digitization of the last mile towards better fulfilment, which directly improves both unit economics as well as consumer experience(which then increases customer spend on Amazon).

Controlling the last mile is critical for control over customer experience. The last mile makes up ~30% of overall logistics expenses.

Amazon has a host of logistics services in the last mile, including crowdsourced deliveries from external contractors (Amazon Flex and Amazon Logistics), Amazon Key to allow deliveries into your home, delivery to car trunks, remote door access to Amazon couriers, Amazon lockers and apartment hubs (Amazon hubs), and distribution by drone (Prime Air) ensure customer convenience.

Again, data is the reason Amazon gets this right:

Route optimization: Optimal routes for delivery drivers are derived from the data aggregated across customers, drivers, connected vehicles, weather forecasts, traffic monitoring systems, and digital and satellite maps.

Fleet planning: Amazon’s fleet management system calculates how many drivers are needed at any given time. It evaluates the weight and number of packages headed to the same destination and matches packages and destinations to fleet availability. This includes determining the order of packing boxes into a vehicle to enable the most effective unloading based on delivery address.

Mapping metadata: Amazon is gathering delivery metadata that puts mapping features into context. For instance, one big challenge for Amazon Flex delivery personnel is parking. Amazon constantly analyses late deliveries and identifies patterns and correlations with:

1) Building type (single address vs multi-address),

2) Access (Deliver at door vs at reception vs in mailroom)

3) Parking facilities (at building vs not)

By correlating delivery times and delays with these variables, Amazon is creating a new layer of delivery intelligence on top of mapping data. This prediction capability can again be opened as-a-service for third party logistics firms.

Amazon’s logistics powerhouse

There’s a lot more to Amazon’s logistics success. Here’s the full teardown for later:

But isn’t delivery a solved problem?

This might make you wonder… isn’t delivery a solved problem?

Aren’t FedEx and UPS well positioned to provide an alternative to Amazon and help all offline retailers effectively solve online fulfilment?

Apparently not.

As explained above, fulfilment requires integration into demand-side data. What are customer purchase habits? How should this inform our supply chain and warehousing?

To respond to this demand-side data, retailers need to ensure capacity, ensure on-time delivery, and service multiple options in the last-mile (in-store, curbside, locker, car trunk, home etc.). In order to do this, retailers need to better diversify their last-mile carriers.

But diversifying last-mile carriers comes with its own set of challenges. First, the landscape of last mile carriers is fragmented with players ranging from tech-native startups to traditional local players with low tech use. Technology integrations are a nightmare. Furthermore, diversification also comes with the risk of losing volume discounts from a carrier, overheads of allocating work and segregating volume across multiple carriers.

Logistics is very good at getting stuff from point A to point B, but not quite as good at rearranging points A and B dynamically and optimizing delivery and returns based on purchasing habits to find the most optimal solution.

Now, FedEx could, potentially, tie up with a large online marketplace to get access to demand-side data but no other player has data at the scale of Amazon. In particular, this problem would largely remain unsolved for the mid-tier players.

This is why FedEx acquired ShopRunner, a Prime-like program that is available across independent retailers. In exchange for 2-day delivery, ShopRunner gains access to your shopping cart across a diverse range of retailers. In this manner, ShopRunner cuts across data silos and creates a consolidated purchasing profile across your shopping carts.

The integration of this consolidated shopping cart data with logistics data helps better solve the fulfilment and returns problem.

This is also why UPS acquired Delivery Solutions. Both FedEx and UPS need demand-side data (drop density data) to selectively grow their fulfilment network in response.

Paths-to-fulfilment for offline retailers

Managing fulfilment and returns is a unique moat for at-scale online marketplaces. Offline retailers looking to compete need:

Access to demand-side data

A responsive supply chain that can act on this demand-side data

Most offline retailers struggle on both counts.

How can offline retailers solve for these issues?

Let’s work through the two variables above - Demand-side data access and supply chain responsiveness - to look at ways in which offline retailers can solve for these issues.

To help us with that, let’s use - what I’ll call - the Fulfilment Effectiveness Spectrum.

There are two ways to move up the fulfilment effectiveness spectrum.

First, you could do what FedEx and UPS did and get access to demand-side data to inform the delivery network.

While every mid-tier retailer has some (but not quite enough) demand-side data, the logistics players are poised to benefit most from acquiring demand-side data. Increasingly, we will see retailers working with logistics providers to share their data and benefit from superior fulfilment. GAP Platform Services - a partnership between GAP and UPS - is one such early example.

The other way to solve this problem is to either get greater control over the supply chain or reimagine the supply chain based on demand data, and hence, deliver greater responsiveness.

Many retailers have taken this path over the past 2 years. Costco Wholesale acquired Innovel for big and bulky last-mile deliveries. Ashley Furniture acquired Wilson Logistics. American Eagle Outfitters (AEO) acquired last-mile startup AirTerra and fulfilment provider Quiet Logistics.

Beyond marketplaces

Business models may evolve with technological shifts but this principle still applies.

I explained in an earlier post why logistics providers have their tasks cut out in a protocol-based ecosystem, unless they gain integration into demand-side data, which runs counter to the ethos and mechanics of protocol-based mediation.

Have a look at the article below to dive deeper into how the topics of this analysis above apply not only to offline retailers but also to emerging ecosystems and the firms that participate within them.

The ONDC conundrum: Where protocols win... and where they don't...

India’s ONDC (Open Network for Digital Commerce) has been the most ambitious decentralized alternative to the centralized e-commerce marketplace model pioneered by Amazon and others. Yet, it has (thus far) struggled to fully deliver on its promise to reorganise the commerce ecosystem through a protocol-based approach.

And if you’d like to write in, just hit reply.

This made me think about Greylocks new moats narrative ...

A key question I have though is about inventory: when does inventory get unbundled?

How fare can Logistics player go without owning inventory or (at least) *owning* suppliers

ONDC seems to be a good step in the direction o both making demand-side data publicly avaible and unbudling inventory what do you think?