In 1849, a swarm of men poured into California, lured by rumours of rivers filled with gold.

This was the Gold Rush, where everyone rushed toward the same valleys and set up camp beside the same creeks.

All drunk on the same hype. All nodding in unison to create consensus theatre.

The smarter ones didn’t dig at all. They sold shovels instead.

Somehow, that’s the metaphor that stays on every time we talk about a gold rush. In a gold rush, they say, don’t dig for gold. Sell shovels instead.

But what if we’re getting our gold rush metaphors not quite right?

Not your neighbourhood gold-digger

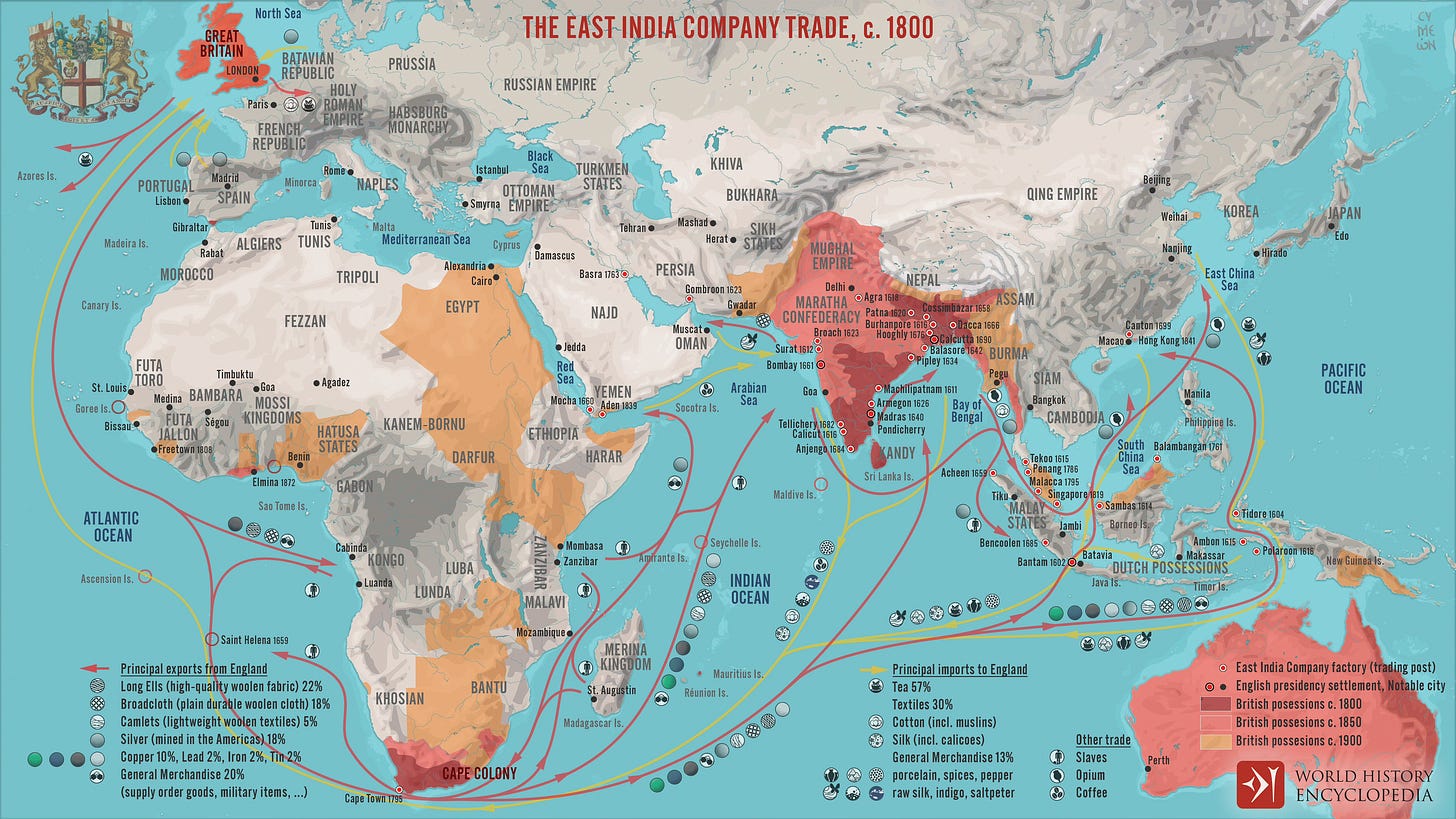

The British East India Company may not have carried shovels, but it was, in every strategic sense, a gold digger.

While others dug for gold, the Company hunted for extractive advantage. It looked for control over trade routes and monopolies on spices, tea, and textiles. It looked for the ability to tax and govern without formal sovereignty.

Why dig through dirt when you could redirect the flow of wealth by owning key control points: the ports, the ships, the legal systems.

The world which the Company set to control and conquer was poorly mapped. Most European fleets relied on intuition and seasonal memory to navigate the seas. But the East India Company was a gold-digger with a plan.

It began to map global wind patterns and ocean currents methodically, to create wind charts, sailing calendars, and routing logic, which saved months on their journeys and reduced shipwrecks.

Instead of bothering with gold and shovels, or even with building better ships, the Company was focused on building maps. Better maps create better strategies for movement.

In fact, mapping didn’t stop at mapping the seas. Mapping India, the Company’s prime gold-digging target, was its most powerful act of conquest.

The Great Trigonometrical Survey of India transformed a complex network of locally governed kingdoms into something that could be centrally governed from London. Maps helped the Company convert a decentralized and fragmented system of landholding and agriculture into standardized, taxable units.

Mapping was governance. And mapping, more importantly, was scalable extraction. Once the land could be standardized, it could be governed and taxed.

The Company knew that the key to a gold rush was not so much in better shovels as it was in better maps. Maps could help locate concentrated value and help the Company insert itself at the point of control.

The shovel-selling trap

The Company used maps instead of shovels. But they were incredibly effective at extracting value.

That’s because in systems defined by uncertainty and competition, better shovels - or superior tools - are irrelevant. What matters far more is knowing where to dig.

Most enterprise AI providers are selling shovels today. Tools that promise to execute familiar tasks faster. Generate presentations and contracts faster. Sell a thousand personalized emails.

This is the gold rush logic of enterprise software. Take something you already do and expand its scale and scope.

The real opportunity lies elsewhere, though. Better execution is good in a stable environment, but in an environment with structural uncertainty, what you. need is better navigation.

Traditional enterprise software is built on the idea of workflow automation. The assumption is that the workflow itself makes sense, the bottleneck is execution.

AI is sold into enterprises today with a similar productivity-first framing. Do more of what you already do in less time with fewer people. It makes for easy demos and shorter procurement cycles.

But it’s also a trap.

When everyone is improving the same workflows at the same speed, the gains become incremental and there is no differentiation or advantage.

Margins go down. and you end up in a commodity race, as the productivity gains paradox sets in. Every competitor has access to the same tools and the same automation. The only way to compete is by lowering cost or increasing volume.

It’s the enterprise version of the vibe-coding paradox.

Over the past decade, I’ve worked with a range of technology firms helping them frame their strategic narrative to clients. And over the past couple of years, I’ve noted a progressive shift that separates the firms who’re getting it right from the ones who are not. What’s common to all of them is one simple distinction:

Stop selling shovels.

Start selling treasure maps.

Shovels sell speed. Treasure maps sell direction.

And whenever a technology positions itself as a way to reduce uncertainty and unlock hidden opportunities, and most importantly, change the basis of competition, it moves from creating mere efficiency to creating leverage.

These solutions command higher margins because they create asymmetric value in ways that others can’t easily copy.

AI and treasure maps

AI lends itself naturally to treasure maps. It has the capacity to uncover hidden relationships across fragmented datasets.

Intelligent solutions can detect small shifts before they escalate and surface weak signals that might otherwise go unnoticed.

In December 2019, before most global health authorities had issued any alerts, the Canadian AI firm BlueDot spotted an unusual pattern in Wuhan. Ironically, it wasn’t analyzing lab tests or viral genomes. It was scanning news reports, flight data, and hospital records in multiple languages.

In 2021, Dataminr detected the U.S. Capitol riots developing in real time before many newsrooms did.

Yet, we continue to package AI solutions like traditional productivity software. Just another way to crank out more of the same work. The value of AI is in showing us what we should be doing differently, not in helping us do more of what we already do.

Most enterprise AI providers miss this - partly for lack of imagination, and partly blinded by hype.

A shovel mindset treats AI as a way to reduce costs

A treasure map mindset treats AI as a way to make better decisions.

Treasure maps rewire the workflow

The shovel mindset drives marginal improvements. The treasure map mindset helps you reimagine workflows and organizational structures.

The rise of Computer-Aided Design (CAD) created this divergence among manufacturers in the 1990s.

Most firms initially adopted it with a shovel mindset. They swapped out pencil-and-paper drafting for digital drawing. This made individual designers more productive as they could easily generate and edit blueprints. But the underlying workflows remained the same.

Boeing, on the other hand, approached CAD/CAM with a treasure map mindset. Instead of digitizing drafting alone, they used CAD to integrate the workflow across design, manufacturing, simulation, and assembly.

With CAD, they could prototype entire aircraft virtually and detect component clashes in advance. This helped better coordinate the workflow across engineering, production, and supply chain.

Treasure maps change the basis of competition

Better and more integrated workflows are interesting, but they’re only a starting point.

Treasure maps are more interesting when they help you dig where no one has dug before, and with that, they change the very basis of competition.

Think of TikTok, a late entrant into social networking, shifting the basis of competition using AI. Unlike Facebook or Instagram, which were structured around known-user social graphs, TikTok redefined the basis of competition through AI-powered content discovery.

It shifted the attention model from who you know to what you engage with, forcing every social platform to rethink its core mechanics.

Shovel AI helps you do what you already do, but more cheaply.

Treasure map AI helps you see what you should be doing instead, and redesign your workflows, organization, and business model accordingly.

Even the way companies adopt AI reflects this.

Facebook and Instagram used AI to optimize engagement on your social graph, and drive more posts, likes, shares. The AI was a shovel to drive better engagement on the legacy friend network architecture.

TikTok uses AI to discover unexpected connections, by elevating content based on behavior, rather than relationships. This ends up creating a network architecture that is decoupled from a user’s existing social capital. Eventually, every competitor realized that this had changed the basis of competition and implemented some version of this for their own platform.

In a fast-moving, uncertain environment, companies don’t win by digging faster. They win by knowing where to dig and where not to.

Building a ‘barcode-native’ company

The distinction between shovels and treasure maps isn’t specific to AI.

It’s a much older pattern that determines who gains leverage in every major technological shift.

In the 1980s, both Kmart and Walmart adopted barcodes.

Kmart treated the barcode as a shovel - a way to move lines faster and improve point-of-sale efficiency.

The technology was slotted into an existing workflow. Nothing changed around it. The same shelf-stocking process and replenishment cycles, just quicker transactions at the register.

Walmart, on the other hand, used the barcode as a treasure map - a way to increase visibility across the supply chain.

Every scan became a datapoint that fed its inventory management engine and let Walmart monitor what was selling, and when and where it was selling.

Instead of relying on manufacturers to tell them what should be stocked, Walmart used its own data to make those decisions. This flipped the traditional power structure between retailers and suppliers. Brands no longer dictated shelf space, Walmart’s data did.

The barcode itself was neutral. For Kmart, it was a shovel to dig faster. For Walmart, it was a map that revealed how value moved through the system, and how that flow could be redirected to its advantage.

Walmart, in many ways, was a barcode-native company - a company that rearchitected its performance and its value chain relationships around the barcode.

The Walmart that emerged couldn’t have existed without the barcode.

This is the essence of building an AI-native company.

If your company’s basis of competition remains unchanged with or without AI, you are not really AI-native.

You are Kmart adopting barcodes for faster checkout.

With AI today, most companies are working like Kmart - buying faster shovels.

The ones that see what Walmart saw in the barcode will succeed in building AI-native companies.

The others will tick off a few checklists, without fundamentally changing the basis of competition.

Selling AI

Every AI vendor eventually faces a choice.

Selling shovels is easy but commoditized. Everyone’s selling speed. Everyone’s pitching cost reduction.

Selling treasure maps is a harder sale, but once you’re in, you’re harder to displace.

If you’re selling shovels, you’re probably demoing to a department head. You’re talking about task reduction, license cost, FTE savings. You’re negotiating against other vendors in the same category and ticking boxes on a procurement checklist.

If you’re selling a treasure map, you’re facilitating a conversation. You’re in the room with someone who owns risk, or growth, or transformation. You’re focused less on demoing product features and more on helping answer the question What’s happening in your business that you can’t yet see?

That conversation is no longer ticking a procurement checklist.

Once implemented, every decision made and every pattern identified by the ‘treasure map’ gets you codified deeper in the enterprise. You start building a growing proprietary graph that reflects how the organization thinks and moves, and eventually, how it competes. Ripping that out of the organization is non-trivial.

Pre-order my upcoming book

This post is based on ideas from my upcoming book Reshuffle.

Reshuffle is now available for pre-orders. All pre-orders leading up to the launch date are at 70% off. (Launching July 20, 2025)

Seeing more with maps

Maps are surprisingly useful beyond gold quests and conquests.

In 1854, London was gripped by a deadly cholera outbreak, and the medical establishment did what it had always done: treat the sick and quarantine the exposed. A classic response built on the assumption that the disease was airborne.

Or in shovel terms, keep digging deeper!

Throw more resources at the known response pattern, without questioning whether the pattern itself was wrong.

John Snow, physician by day and systems thinker by night, approached the crisis differently.

Instead of focusing on treatments, he turned to mapping. He plotted the locations of cholera deaths on a street-level map of Soho and began looking for spatial patterns.

Mapping revealed, quite curiously, that deaths were clustered tightly around a single water pump on Broad Street. Snow hypothesized that the water, not the air, was the source of infection. When the handle of the pump was removed, the outbreak quickly subsided.

This wasn’t a medical breakthrough in the traditional sense. Snow didn’t invent a cure or discover a new drug. He wasn’t even using anything to do with his training.

But he had shifted the frame.

It’s hard to overstate how powerful this was. Snow didn’t have more data than his peers, but he did have a better way of seeing it.

That is the essence of Treasure Map AI. You see what others don’t see, simply because you’re asking better questions, filtering the right answers, and exercising judgement.

Shovel AI can help you dig faster.

But when speed is cheap, what becomes scarce, and therefore valuable, is knowing where to dig with clarity.

To sell treasure maps, you need to know how to sell curiosity, curation, and judgment.

Read more on this at:

Curiosity: Choosing which path to pursue

In the early 1880s, the Transvaal region of South Africa drew a wave of prospectors looking for gold.

They had shovels and all agreed on the same assumption that gold, as in other places, would be found in surface-level quartz reefs.

Yet this pattern of extraction quickly ran into diminishing returns. Surface deposits yielded only modest results.

George Harrison, a carpenter with no formal training in geology, was curious about something else. He was fascinated with the area’s strange conglomerate rock formations. Harrison noticed small but consistent gold traces deep in the rock. His curiosity helped him identify what would become the Witwatersrand Basin, the single largest gold deposit ever discovered.

Most miners were using shovel logic to get to faster, cheaper digging on assumed deposits.

George Harrison used treasure map logic to create a better model of where value as likely to be found, based on his understanding of the region’s geology.

Harrison’s curiosity had changed the basis of competition. Surface-level digging of quartz deposits required shovels and muscle power. But deep mining required technology and capital investment, alongside the coordination of a more complex labor system. This eventually led to an entirely new model of mining. Thus far an unstructured, informal activity, the opportunity in going deeper justified the capital investment needed to develop deep mining technology, and led to the creation of consolidated corporate mining houses, like Anglo American,

This shift, from effort-based competition to insight-driven competitive advantage, is the basis of Treasure Map AI. It recurs in industries where the basis of competition is disrupted by a better underlying map of where value sits.

TikTok’s insight of building a social network without a social graph is a similar modern day example. The platform’s For You feed did not rely on who a user followed but on what they interacted with. While most other social networks were using AI to improve their legacy recommendation engines and feeds, TikTok redefined the basis of network creation on a social network. Creators no longer needed large networks to find an audience. Discovery was decoupled from relationship.

In both cases - Witwatersrand and TikTok - the initial disruption was not a function of better tools but of a better framing. Once that new frame was validated, the industry reorganized around this new basis of competition.

Curiosity creates better maps and better maps shift the basis of competition.

Curation: Choosing what to elevate and what to exclude

But curiosity alone is not enough.

In the 16th century, most European powers were curious about China as an opportunity for conquest or trade. They wanted to fit China into their own map of the world and strategize about it within those maps.

The Jesuits realized that the only way for China to fit into a map of the West was to build that map the Chinese way.

Jesuit missionaries like Matteo Ricci learned Chinese and adopted Confucian dress, which gave them a path to introducing European scientific knowledge into the court’s existing worldview.

Ricci filtered European astronomy and cartography using a Chinese lens, to elevate elements like solar calendars, that would seem most impressive, while excluding religious dogma that would trigger resistance.

This selective curation granted the Jesuits extraordinary influence in the Ming court. Ricci’s 1602 Kunyu Wanguo Quantu, the first Chinese world map incorporating European geography, rearranged China’s understanding of global space. And it bought the Jesuits decades of diplomatic access.

With the extent of Western knowledge at his disposal, Ricci could have impose his world view and his map on the Chinese. Instead, he used curation to bring out the selective things that would change the court’s perception of its place in the world.

Treasure Map AI acts the same way to help companies reframe their competitive landscape.

Traditional BI tools operate with a shovel mindset. They automate routine slicing and dicing of structured data. You still need to be curious to ask the right questions. But the tool only curates what’s already defined and expected. It makes reporting faster and more accessible. But on the assumption that someone already knows what matters. The bottleneck it’s solving is retrieval and distribution of what matters.

Palantir, by contrast, adopts more of a treasure map mindset. Palantir obviously doesn’t compete with BI tools - its customers are fundamentally different. It helps organizations work with unstructured data streams, across logistics chains, satellite imagery, financial records, and more to elevate non-obvious connections that its users don’t see yet. It helps to trace weak signals before they become threats and reframe operational blind spots into points of intervention.

Through this act of curation - elevating certain signals and excluding others - Palantir builds a new map that helps make a complex operational and competitive landscape actionable.

Judgment: Knowing how to act on what you find

Curation comes from the most unlikely of sources. We trust a tire manufacturer, for instance, with curating the world’s top restaurants.

A Michelin star can make or break a restaurant. But its origins had little to do with gastronomy and a lot to do with tires.

At the turn of the 20th century, and long-distance travel was a novelty. So Michelin, a tire company, needed to get people to drive more, so that they’d need to replace tires more often.

But to drive more, people needed destinations.

So in 1900, they published the first Michelin Guide, which included maps, repair instructions, hotel recommendations, and lists of restaurants along major routes. Over time, as travel grew more common, so did the guide’s ambitions. In 1926, Michelin began awarding stars to restaurants that were worth stopping for. By the 1930s, it introduced a three-star rating system, with anonymous inspectors and rigorous standards.

The tire company had become the world’s most trusted curator of culinary excellence.

The story gets more interesting though.

The Allied invasion of Normandy in June 1944 required a deep understanding of French road networks, bridge conditions, elevation gradients, and choke points.

Ironically, the best maps available at the time weren’t classified military assets. They were the Michelin Guide’s road atlases.

By 1939, when WW2 broke out, Michelin guides were widely considered among the most accurate and up-to-date topographical references available. When war broke out, Michelin ceased publication of its regular guidebooks, but the 1939 edition remained in circulation.

Michelin had invested in curation - of restaurants, yes, but also of roads. The fact that Michelin’s cartographers had focused on usability for peacetime travelers ironically made them perfect for wartime maneuvers.

But those maps needed to be reframed from a road atlas to a wartime operating system. This was the act of judgment that gave Allied intelligence an unfair advantage in storming Normandy.

Allied intelligence officers and logistics teams used Michelin’s 1939 maps to plan troop movements after the beachhead. These maps helped determine which roads could handle tank columns, which bridges needed reinforcement, and how to route convoys without creating bottlenecks.

Maps are built through curiosity and they shape our perception of the landscape through curation. But judgment helps apply them in ways that alter what an organization can perceive and act on.

Stripe Radar plays a similar role in the world of payments. Most fraud detection tools operate like traditional road maps. They tell you where known risks are, by categorizing usage anomalies, identifying geographic risk zones, and scoring transactions based on patterns of past fraud.

Instead of building a better fraud map, Stripe Radar reimagines how that map can be used. Stripe understood that the value was less in listing every possible fraud signal and more in shaping how merchants interpreted those signals and how they acted on it. Judgment was key.

Radar isn’t your usual alert-based system. It acts more like a customisable layer within the payment experience, where individual companies can customize their risk posture and choose the trade-offs that matter. Some may prefer higher tolerance and faster throughput, others may opt for security and dispute prevention. More importantly, it serves these fraud signals across the enterprise customer flows, refund handling, even pricing strategy.

Radar reframes fraud detection from a backend security task to a front-line business decision tool.

Michelin’s road maps, originally designed for peacetime travel, became central to wartime logistics. Stripe’s fraud graph, designed to stop bad transactions, became the foundation for designing smarter customer experiences and competitive differentiation.

This is what distinguishes a shovel from a treasure map.

Seeing what matters

Good maps eventually make you more curious.

The thing about maps is you don’t need to see everything. You need to see what matters and what can be acted on.

This is why curiosity, curation, and judgment are so central to building competitive advantage, whether as individual workers or as organizations, in this age.

In the early 20th century, London’s underground transit map was a tangled mess. It was geographically accurate as a map should be. But commuters had no clear mental model of how to move through the system. The map was technically correct, but practically useless.

That was until Harry Beck came along. You see below what happened next.

Beck, an electrical draftsman, treated the subway like a circuit diagram. Instead of mapping stations to their true geographic coordinates, he focused on usability. Straight lines. Even spacing. Logical connections.

The map wasn’t entirely true, but it helped you see what mattered.

Beck’s design has since influenced metro maps across the world.

That’s what Treasure Map AI does. It curates to elevate what matters and exclude what doesn’t. It empowers you with better judgement. And once you see that it works, it leaves you curious for more.

Love your analysis in this piece! Now if we could only avoid the colonial and extractive horrors of the EIC, and create a community-centered AI treasure map conglomerate.

This article is so helpful as I try to figure out how what we are teaching people about AI ties to the marketplace. Thank you for helping me structure my thoughts a little better by "mapping" the concept that we are not selling more AI training, but how to work with AI with a new mindset and AIQ - AI Emotional Intelligence. That is our "map" to everyone else's "shovel". Now to go explore how we can expand that like Beck and others did with their concepts. Love this! ❤️